Torah First: The Judicial Revolution No One is Talking About

Israeli headlines have been dominated by the proposed legal reform of Justice Minister Yariv Levin, but below the radar, buried deep in the coalition agreements, Likud has agreed with its partners to enact an equally dramatic revolution, which would split the Israeli judicial system and grant rabbinical courts the same powers as any other court. ‘You don’t need to be an expert to recognize that there’s more chance now of the legislation being passed.’ A special Shomrim report

.jpg)

.jpg)

Israeli headlines have been dominated by the proposed legal reform of Justice Minister Yariv Levin, but below the radar, buried deep in the coalition agreements, Likud has agreed with its partners to enact an equally dramatic revolution, which would split the Israeli judicial system and grant rabbinical courts the same powers as any other court. ‘You don’t need to be an expert to recognize that there’s more chance now of the legislation being passed.’ A special Shomrim report

.jpg)

Israeli headlines have been dominated by the proposed legal reform of Justice Minister Yariv Levin, but below the radar, buried deep in the coalition agreements, Likud has agreed with its partners to enact an equally dramatic revolution, which would split the Israeli judicial system and grant rabbinical courts the same powers as any other court. ‘You don’t need to be an expert to recognize that there’s more chance now of the legislation being passed.’ A special Shomrim report

Benjamin Netanyahu and Aryeh Deri at the cabinet meeting. Photo: Reuters

Chen Shalita

January 12, 2023

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

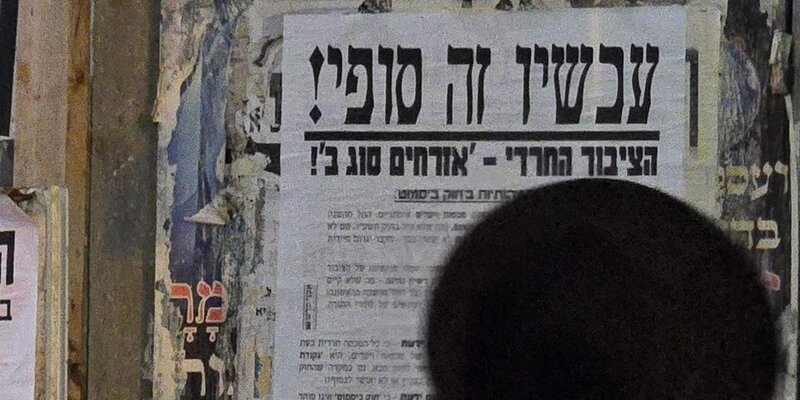

An ultra-Orthodox businessman buys a cellular communications company and adds a new clause to the contract signed by all of the company’s customers: Any dispute between the company and its customers must be settled in the Rabbinical Courts. What happens if a customer wants to sue the company over a faulty device, negligent service, or any other matter? Whether secular or religious, they cannot seek redress in the courts. Instead, the only address for their complaint is the Rabbinical Court.

Does that sound like a flight of fancy? It’s not, according to the coalition agreements that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu signed with Shas, United Torah Judaism, Religious Zionism, and Noam, the single-MK party of Avi Maoz. In each and every one of them, there is an agreement that the authority of the Rabbinical Courts will be expanded to include what is known in Jewish law as Monetary Law – in other words, civil matters – if both parties agree, of course. Whether or not that agreement is given willingly is another matter and one we shall examine below.

Although this move is not mentioned as part of the public controversy over the proposed legal system reform, which Justice Minister Yariv Levin introduced as soon as he was appointed, it is another step toward changing the Israeli judicial system.

“This is another step in the tsunami of moves designed to increase the Halakhic element in our daily lives,” warns Prof. Zvi Triger from the Haim Striks School of Law at the College of Management Academic Studies, who specializes in family and contract law. “[Halakhic] Monetary Law isn’t appropriate for the economy, for the sophistication and values of modern society. The way that facts are ascertained is different. There aren’t the protections that exist in civil law. In Halakha, for example, interest and linkage. Most rabbinical judges do not feel obligated to contract law and are divided over whether laws relating to planning and construction apply to them. Moreover, rabbinical courts do not see themselves as obligated to the principle of equality or to the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty. They do not see themselves as bound by any constitutional or civic principle. It appears specifically in the Rabbinical Judges Law, which says that judges have no higher authority than the Torah.”

Dr. Rafi Reches, the deputy legal advisor to the rabbinical courts, is keen, of course, to allay any fears. “As far back as 2018, there was a memorandum of law that was passed at its first reading, and we accepted laws that we would be subject to. I believe that the proposed legislation that will be submitted to this Knesset will be similar in nature. And that there will be clear agreement, wording coordinated with the Justice Ministry, which will ensure you go there from your own free will.”

But now most of the coalition partners are talking about giving the Rabbinical Courts the power to pass judgment, not just engage in mediation.

“Because why should rabbinical judges run to the District Court to get approval for a verdict, as the rules of arbitration dictate? We are proposing a court, the ruling of which can be challenged in the Great Rabbinical Court of Appeals and, after that, in the Supreme Court. The difference will be that our processes will be more efficient and quicker than civil courts and our fees will be lower. You also won’t need a lawyer because the rabbinical judge leads the hearing.

“At the time, [Avigdor] Lieberman was the only coalition member who opposed the legislation, so it did not progress. Now we view that as a retreat for the sake of making progress. You don’t need to be an expert to recognize that there’s more chance now of the legislation being passed.”

“The danger is not just when it comes to corporations,” Triger says. “Even the landlord from whom you rent an apartment can insist that the tenancy agreement includes a clause mandating rabbinical judgment.”

Would it be so terrible if cases went before a rabbinical judge?

“Women are not eligible to testify according to Halakha, so, as a woman, you would find yourself in an immediate position of inferiority. And if you testify nonetheless, because the court manages to find a way around that restriction, to maintain their power and not lose cases, you would be considered less credible than a man, just because of his gender.”

Is it also problematic for secular men?

“According to Jewish law, a man who does not observe Shabbat is not entitled to testify. The rabbinical judges would be more inclined to believe an ultra-Orthodox man than a secular one, someone who is national-religious or a Reform Jew. And, once again, in order that secular people will appear before them in divorce cases, the chief rabbis ruled that the rabbinical courts cannot disqualify the testimony of a secular man. But the underlying belief of the rabbinical judges, the vast majority of whom are ultra-Orthodox, is that secular men are not to be given the same level of credibility – to say nothing of someone who is not Jewish.”

“This is another step in the tsunami of moves designed to increase the Halakhic element in our daily lives,” warns Prof. Zvi Triger. “Rabbinical courts do not see themselves as obligated to the principle of equality or to the Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty. They do not see themselves as bound by any constitutional or civic principle. It appears specifically in the Rabbinical Judges Law, which says that judges have no higher authority than the Torah.”

‘The Public Doesn’t Understand the Significance’

Before you rush off to find the last contract you signed, we should make it clear that the Rabbinical Courts do not currently have the authority to rule on civil disagreements unrelated to matters of personal status, such as marriage and divorce. What, then, can they rule on? According to the law, rabbinical courts have exclusive authority over marriages and divorces between Jewish couples living in Israel and, if all the sides agree, over matters relating to custody, alimony, and inheritance. On some issues, such as the division of property, there is a race to determine which branch of the judiciary handles the case. Whichever party is quicker to open a file determines whether the case will be heard in the Family Court or the Rabbinical Court. And still, in circumstances where there is “parallel authority,” the rabbinical judges are obligated to take the laws of the State of Israel into account rather than the law as per the Torah (except in cases of alimony, where the Rabbinical Court rule according to halakha).

So, the clauses in the various coalition agreements demanding that the Rabbinical Courts be recognized as judicial authorities for civil matters or arbitration, without the need for a civil court’s approval (which is fairly similar), constitute a real revolution.

Where does this demand come from? “The rabbinical courts have never been granted the authority to rule on matters of civil law,” explains Dr. Hanan Mandel from the Law School of the Ono Academic College. “During the period of the British Mandate, they took upon themselves cases dealing with financial law, but only as arbitrators. The authorities do not recognize an arbitrator’s ruling without approval from the courts. You can’t take it to the bailiffs or the Interior Ministry unless the District Court has signed off on it.”

Is that why the coalition agreements stress that the Rabbinical Court rulings will be valid because they don’t want to rely on civil court approval?

“Exactly. In the 1990s, Justice Mishael Cheshin would often comment that he couldn’t understand how the Rabbinical Courts were taking cases on the side as arbitrators, but there was no specific appeal that necessitated the Supreme Court to discuss the issue – until the Sima Amir case in 2006.”

What was that about?

“When Sima Amir divorced her husband in the Rabbinical Court, both parties signed an agreement that they would seek redress exclusively in the Rabbinical Courts in any future property dispute between them. When Sima understood the ramifications of this for her, as a woman, she petitioned the Supreme Court, which ruled that the Rabbinical Courts did not have the authority.”

They were already divorced, the gett [Jewish religious divorce certificate] had been issued. Why should they ever have to meet in court again?

“Because of questions about the children, like alimony and custody. Or when the divorced couple were also business partners and, for reason of economic viability, that partnership continues after the divorce. The arbitrations that took place until 2006 in the Rabbinical Courts dealt not only with interpersonal relationships but also with civil disputes. Under then-chief justice Ayala Procaccia, the Supreme Court rules that a state-run rabbinical court, which has all the symbols of the state, cannot take arbitration jobs on the side unless the Knesset grants it that authority by law.”

What was that ruling?

“Since the computer system didn’t let us manage the registering of cases, some rabbinical courts kept on [taking arbitration cases] by keeping hand-written records of arbitration in a notebook, but, in the end, that also came to an end. Now, there are private courts for financial matters which conduct private arbitrations, just as there are in secular society.”

But efforts to restore the former glory of the rabbinical court never stopped. In fact, they were redoubled – from arbitration to judicial standing.

“These kinds of clauses appeared in the coalition guidelines of all of Netanyahu’s previous governments. What’s new this time is that they are part of a broad package of reforms in democracy. Legislation inspired by such ideas has been thwarted in previous Knessets because, in the previous coalitions that Netanyahu assembled, there were those who recognized that it would be problematic. In this government, there are no liberal voices alongside Netanyahu.”

And the motivation is different.

“Therefore, if Netanyahu agrees, it will happen. So far in this Knesset, no new proposed legislation has been submitted, so anything could happen. In the past, when such legislation reached the various Knesset committees, revisions were proposed that toned down the original proposal. I do not see any such revisions in the most recent coalition agreements.

“On the one hand, it is standard practice to include a lot of red herrings in the agreements so that they can pass the initiative and say, ‘But look how we exempted the labor laws and we added a law giving women equal rights.’ On the other hand, given the majority of religious rightists in this coalition, it’s far from certain that they will even try to soften it. As a religious person, I say there’s a huge problem granting this authority. It’s another way of strengthening the religious motif and turning us from a Jewish and democratic state to a Jewish religious state.”

Do you expect any public opposition?

“The public does not understand the significance of the move. People will ask, ‘What’s this got to do with me? I don’t have any interaction with rabbinical courts. Let the Haredim deal with their own issues.’ And the government will market it as a solution to easing the situation for the overburdened courts because religious people will go there instead of the civil courts. That’s not accurate since some of them, in any case, do not use the state’s courts and, in any case, they would add to the line of people waiting for an appointment to get divorces – who have no choice but to do so through the Rabbinical Courts.”

Maybe it’s just a way of creating jobs?

“And that is why I do not foresee opposition from the private financial courts. If judges in private courts lose their source of income because their potential clients go to a rabbinical court, they will also go to work there, where they will get the salary of a civil servant.”

“If we see the public coming in droves,” Reches says, “and our capacity for handling them is overwhelmed, we will ask the state to provide us with more judges. In the meantime, we believe that we can cope with it and that Monetary Law will only be a percentage of the cases we hear.”

What percentage?

“I don’t want to throw out numbers.”

“Jewish law is full of justice,” says Rabbi Mordechai Bogayev, a certified rabbinical judge and head of the Yesodot Institute for Jewish Law. “It came from the Torah, which is divine, and there is nothing more just than how God created the world with his laws. There’s no reason for us to rely on judicial systems and laws handed down to us by nations that once ruled over us. With all respect to the pain suffered by some sections of society, there is no reason not to allow someone who wants to be judged by a rabbinical court to do so. It is a return to our tradition, and no one is saying that it will be compulsory.”

“As far back as 2018, there was a memorandum of law that was passed at its first reading, and we accepted laws that we would be subject to,” says Dr. Rafi Reches, the deputy legal advisor to the rabbinical courts. “At the time, Lieberman was the only coalition member who opposed the legislation, so it did not progress. You don’t need to be an expert to recognize that there’s more chance now of the legislation being passed.”

‘If it Bothers You That There are No Women Judges, Don’t Use the Rabbinical Courts’

The question of coercion versus the free will of all the parties is a major stumbling block – even if we assume that the word ‘agreement’ is not erased gradually over the years, as part of a ‘foot in the door’ policy, as many pessimistic jurists predict. “Ultra-Orthodox society has power,” says a senior jurist who knows the issue well. “A lot of economic and societal pressure will be applied to ensure that individuals and businesses come to them, and there’s the issue of the siruv [a form of contempt of court order issued by a rabbinical court in an effort to compel action by an individual]. Societal sanctions are imposed against anyone who refuses to be judged by Torah law. Although the Supreme Court has banned rabbinical courts from doing so and the attorney general has issued similar instructions to the private courts, it still happens verbally.”

“Being judged by a religious court is being judged by an inequitable legal system,” says Prof. Ruth Halperin-Kaddari, the head of the Rackman Center for the Advancement of the Status of Women at Bar-Ilan University and head of a coalition of groups opposed to the move. Earlier this month, Halperin-Kaddari sent a letter on the matter to Levin. “To take a judicial system that is affiliated to the state, with all the symbols of the state, and to give it this kind of power – it’s terrible. When people get a summons with the official emblem of the State of Israel, they won’t understand that they have the right to refuse. They will see it as a mandatory summons.”

Reches disagrees. “There’s no change in the status quo here. A large part of the public wants it and we won’t force it on anyone who says, ‘This is 2023 and it’s not appropriate for me.’ Agreement will be given the moment the case is submitted and not because of some contract you once signed. There will be no such thing as an agreement in advance. We are aware of these problems. And when it comes to Monetary Law, there’s no difference as far as we are concerned between men and women, apart from when they are a couple. We are subordinate to the existing civil law, otherwise, our rulings would not have any validity, and we are also subordinate to the laws that protect workers’ rights and the rights of people with disabilities. There’s nothing to worry about.”

If you are subordinate to so much legislation in Israel, why do we need you?

“Because the outcome will not always be the same outcome from a civil court. When there is a debt, for example, there is a seven-year statute of limitations in civil court; there’s no such thing, according to Halakha. We combine Halakha and the law.”

None of this impresses Halperin-Kaddari much. “Even when the rabbinical courts are subordinate to civil law, they find creative interpretations or simply ignore it – especially when it clashes with human rights and fundamental principles of equality. It is not an equitable system. There are no female judges in the rabbinical courts, just men, most of whom have studied Torah and not law. Why should the state fund a system that is, by definition, not equitable? In no Western country does religion have such power when it comes to marriages and divorces, so why expand it to other areas? And why does one country need to parallel judicial systems based on different concepts of justice when it is the Knesset that passes laws here?”

Reches responds: “It is true that in every other country in the world, there is just one judicial system, but we are the state of the Jewish People, that is part of what sets us apart. Just like we have the Rabbinate, we also have rabbinical courts, and we offer people the opportunity for Halakhic rulings – something that has been exclusively ours for two thousand years. It is also true that the rabbinical judges have primarily studied Torah, but they also undergo legal training. And we will train a group of judges who will study labor laws thoroughly. And anyone bothered by the fact that there are no female judges, shouldn’t come to the rabbinical court. Even though that’s what it says in the Code of Jewish Law and that’s the way it has always been in Judaism.”

The coalition agreements only talk about Jewish courts. Is this, in fact, a subsidized bonus for Israel’s Jewish citizens alone? What about members of other religions who want their own judicial system?

“Israel is a Jewish and democratic state, which is the perfect combination. The lawmakers have already determined that if the courts encounter a lacuna, they can rule according to the principles of Jewish law; we are offering a judicial system with meaning.”

Halperin-Kaddari has this to say on the matter of discrimination: “In the coalition agreement with Shas, they make do with saying that only one of the parties needs to be Jewish. Do you understand how absurd that is? You are forcing a non-Jew to be judged according to Torah law – and that person, by virtue of the fact that they are not Jewish, will be at a disadvantage. Can you imagine a building contractor dragging his Thai or Palestinian workers to a rabbinical court? What chance would they have?”

“Legislation inspired by such ideas has been thwarted in previous Knessets because, in the previous coalitions that Netanyahu assembled, there were those who recognized that it would be problematic. In this government, there are no liberal voices alongside Netanyahu,” says Dr. Hanan Mandel. It’s another way of strengthening the religious motif and turning us from a Jewish and democratic state to a Jewish religious state.”

‘Bringing Jewish Israel Closer to Democratic Israel’

Those who oppose expanding the authority of rabbinical courts give as an example the research of Prof. Ron Kleinman, chair of the World Association of Jewish Law and a lecturer in Jewish Law and Tort Law at the Ono Academic College. Kleinman studied the rulings of rabbinical courts acting as arbitrators in cases relating to labor law. He uses the rulings whereby the rabbinical courts rejected suits filed by female kindergarten teachers employed in schools operated by the ultra-Orthodox Agudat Israel movement to highlight the problematic nature of rulings based on Torah law.

The employees signed a contract agreeing to waive all of the fundamental social rights – something that Israeli law would not have allowed. However, the rabbinical judges rejected their suits, saying they had agreed to those terms when they signed the contracts. “Most of the rabbinical judges,” Kleinman wrote, “gave rulings that violated the basic labor laws of the country since they found Halakhic justification for the workers waiving their rights. They ruled that the kindergarten teachers agreed to waive their welfare rights in solidarity with the importance of their places of work or that the undertakings given by the managers of these institutions to the Education Ministry, whereby they agreed to pay the teachers in accordance with the law, does not hold water in terms of Halakha. Some of the rabbinical judges even expressed their concern that full payment of welfare rights would lead to the collapse of ultra-Orthodox learning institutions and a decline in Torah study.”

Kleinman inferred from this that the ultra-Orthodox worldview of the rabbinical judges also influenced their rulings on civil and financial matters, which have nothing to do with family issues. What does Dr. Reches, the deputy legal advisor to the rabbinical courts, have to say about that? “In the past, there were some rulings from some judges that ignored protective laws. That won’t happen again.”

In light of his research, one could be forgiven for assuming that Kleinman is opposed to the expansion of the rabbinical courts’ powers. Surprisingly, however, in a conversation with Shomrim, he expressed support. “I stand by my criticism, but the situation is different today,” he explains. “There are things that have been agreed upon in previous discussions over this legislation, and I hope we can continue from that point. Moreover, the younger generation of rabbinical judges is more open, they know more about the laws of the state and Supreme Court rulings than in the past. There’s more awareness today.”

And you’re confident of that?

“That’s better, in my view, than the private courts which offer mediation on financial matters, where they don’t even keep an ordered protocol, there are no explanations to the rulings, at most they offer three or four lines of their ruling, they never publish their rulings. Better to go to the rabbinical courts. Rabbinical judges will be trained in the laws of the land. It’s not beyond them. I know you are skeptical, but I believe it will bring Jewish Israel closer to democratic Israel.”