No State, No Status: The Israeli-Born Kids Who Aren't Citizens of Any Country

Tens of thousands of children born in Israel are growing up without an identity card. They receive welfare services and education, but officially they hardly exist. Even those who are wards of the state and who live in boarding schools or foster families remain transparent, and, once they become adults, they are left to their own devices. "I don't have an ID card, so I certainly can't get a passport. It's even harder for me to find a job," says 20-year-old Roni. A special Shomrim report

.jpg)

.jpg)

Tens of thousands of children born in Israel are growing up without an identity card. They receive welfare services and education, but officially they hardly exist. Even those who are wards of the state and who live in boarding schools or foster families remain transparent, and, once they become adults, they are left to their own devices. "I don't have an ID card, so I certainly can't get a passport. It's even harder for me to find a job," says 20-year-old Roni. A special Shomrim report

.jpg)

Tens of thousands of children born in Israel are growing up without an identity card. They receive welfare services and education, but officially they hardly exist. Even those who are wards of the state and who live in boarding schools or foster families remain transparent, and, once they become adults, they are left to their own devices. "I don't have an ID card, so I certainly can't get a passport. It's even harder for me to find a job," says 20-year-old Roni. A special Shomrim report

Roni in Tel Aviv. Photo: Bea Bar Kallos

Daniel Dolev

June 30, 2022

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

R

oni is almost 20 years old. Her optimism and her smile give no hint to her troubled past and perhaps even belie it. When she was less than 18 months old, she was hospitalized with alcohol poisoning. Shortly thereafter, welfare authorities removed her and her brother, Alon (whose name, like all of the minors mentioned in this article, has been changed), from the custody of their parents, migrant workers from Ghana, and moved them in with a foster family.

Roni says that her father has been in and out of Israeli prisons and that she and her brother have almost no contact with him. He was never a father figure for them. Their mother, as far as they know, returned to Africa, where she apparently passed away. Roni and Alon were raised by their foster mother, but a few years ago, she was diagnosed with cancer. She died when Roni was 14, and her brother was 15 and a half – and they were sent away to boarding school.

It was only then that Roni understood that she had no legal status in Israel. The Interior Ministry gave her a fictitious passport number for those times when she would need to provide some kind of identification number – but, in practice, she had no real ID card, and having the number was of practically no significance. "At school, for example, when students needed to present an ID card to sit their matriculation exams – I didn't have one," she says. "Every time the invigilator asked for an identification card, I needed to call someone from the school to identify me. Then there was the school trip to Poland, which I couldn't even consider joining. I didn't have an ID card, so I certainly could not get a passport. Even finding work is pretty much impossible for me."

According to an estimate from the Interior Ministry's Population and Migration Authority, submitted in response to a request by Shomrim, there are currently around 30,000 minors living in Israel who are defined as having no official status. For the most part, these are the children of foreign workers who were in the country illegally – having overstayed their work visa, for example. But there are also 134 children who were removed from their parents' custody by Israeli welfare authorities and now reside with foster families or some other framework outside the family home. In other words, they are under the care and responsibility of the state.

Not having an official status in Israel might sound like a purely bureaucratic problem, certainly to anyone who is already a citizen of the country. People with citizenship tend to take it for granted and rarely consider its benefits. But for those who are neither citizens nor residents, the lack of official status is present and felt in every aspect of their lives. Statusless people do not have an identification document, as Roni discovered when she was sitting her matriculation exams – and they cannot obtain a passport or a driver's license. They also can not open a bank account, and even if they happen to have a work permit, most employers – certainly in more lucrative fields – are wary of employing them. Renting an apartment without any form of identification is also almost impossible.

The case of Roni and her brother is even more complicated since it turns out that they are not just statusless in Israel, they are also stateless. In other words, they do not hold citizenship of any country and are not entitled to it. Their parents' country of birth, Ghana, refuses to recognize them. Their mother apparently originally entered Israel on a Liberian passport, but, in any case, Liberia does not recognize them as its citizens. During legal hearings into their case, it was suggested that their father was actually from Sierra Leone, but that country also does not recognize them as its citizens.

Statusless people do not have an identification document, as Roni discovered when she was sitting her matriculation exams – and they cannot obtain a passport or a driver's license. They also can not open a bank account

Being born here means nothing

According to Interior Ministry regulations, when someone is recognized as stateless, they are entitled to a B1 work visa. Within a few years, that person is supposed to be granted temporary residence status in Israel, which must be renewed annually. However, this rule applies only to people who entered Israel via a recognized border crossing, not people born here. Therefore, it does not apply to Roni and Alon.

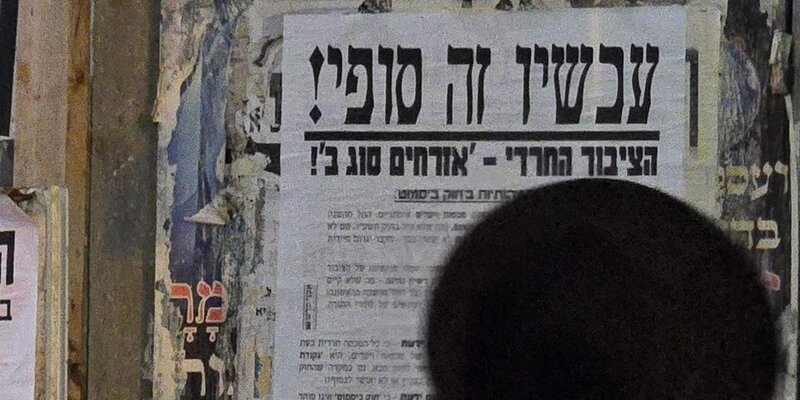

As a result, for the past 15 years, Roni and her brother have been wards of the state – even though the state has done nothing to help them get official status. Because of the sensitivity of the issue of stateless and statusless children, it is hard to believe that this is inadvertent. The issue exploded into the headlines several times over the past decades when Israel sought to expel hundreds of children of foreign workers who were born here to their parent's countries of origin – even though they were completely unfamiliar with those countries.

In 2010, the cabinet adopted a resolution that regulated the status of some of these children and even some of the parents, but the resolution did not apply to minors who had been removed from their parents' custody and were, in fact, transferred to the state's care. This is not the first time that the state has ignored the problem.

In 2013, the State Comptroller published a far-reaching report on the handling of children with no status in Israel. The report stated that these minors are given access to welfare services, education, and healthcare – but did not go into the issue of who is responsible for regulating the status of minors who have been removed from their parent's custody.

Three years after the publication of that report, the Welfare Ministry, as it then was, issued a directive on how to handle statusless children, and, for the first time, the state commented on children removed from their parent's custody. According to this directive, and in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, of which Israel is a signatory, "as a rule … the interests of the minor are best served if he or she is raised by his or her parents or by the extended family and, this being the case, efforts should also be made to locate the minor's relatives in the parents' country of origin." Therefore, when considering whether to remove a child from the parent's custody, the Welfare Ministry's International Welfare Service is brought into the picture to try and locate the minor's relatives in one of the parent's home countries and to establish a line of communication with the welfare services in that country.

But what happens when a minor has no extended family to take custody of them? According to the directive, before any long-term decision is reached as to the fate of the minor, the social worker employed by the local authority should contact the Population and Migration Authority in the Interior Ministry and ascertain the exact status of the minor, the parents and "whether there is any possibility of resolving the minor's status in the country."

This information is supposed to be considered by the ministerial committee that decides on the minor's future. However, the directive does not address the question of who is supposed to resolve the issue in practice – even if there is no choice but to allow the minor to remain in Israel.

.jpg)

The issue exploded into the headlines several times over the past decades when Israel sought to expel hundreds of children of foreign workers who were born here to their parent's countries of origin – even though they were completely unfamiliar with those countries

From embassy to embassy

"I think the state should have looked at our case differently from other cases," Roni says. "They should have seen that we really were born here and that we have the right to remain here; that we want to grow up here and raise our children here and become part of society. From the moment that they realized that something was wrong here, that they were dealing with someone born in Israel but who does not have any status – and we know full well that we have the right to be here – I think that they should have done everything to make it happen and not wait so many years by procrastinating."

It was only when Roni and Alon turned 18, therefore, and were no longer minors, that they began their journey to get an official status from Israel, with the help of Dana Yaffe, an attorney who heads the Hebrew University of Jerusalem's Clinic of International Human Rights. "The first thing that we did was to go with the children to the embassies of all those countries they may have some connection with and ask whether they recognize them as citizens," says Yaffe. "We were either told that they do not recognize them, or we got no direct answer and were just shunted from one official to another. A simple check revealed that assuming that the mother was indeed from Liberia, that her children did not know her, and that she died several years ago, according to Liberian law, they have no right to citizenship there. The father is in Israel, apparently because there is nowhere to deport him to. He is either from Ghana or Sierra Leone – but neither of those countries recognizes him. These are all things that the State of Israel could have done better than us – maybe with the Foreign Ministry's involvement – but it did not.

"The moment that we were able to prove that they were stateless, the question of their right to status in Israel became much more pressing," Yaffe adds. "This is not a case of children of foreign parents who were born in Israel and might someday be able to move to another country. They have no other place in the world but Israel. They were born here, and, in the end, the state is responsible for them, too. There is something absurd in giving these children welfare services but, at the same time, acting as if something will change in the future and therefore there's no need to solve their citizenship problem."

Roni hopes to be granted Israeli citizenship so she can pursue her dream of serving in the Israel Defense Force. "I wanted to join up, and I looked into the possibility of volunteering, but I couldn't because I am not a citizen of the country," she says

Even after an official request for status was submitted, Roni and Alon's tribulations were not over. The Interior Ministry agreed only to grant them a B1 visa – the same visa granted to foreign workers. When they challenged that decision in the Population and Migration Authority's appeals court, the Interior Ministry even claimed, among other things, that the siblings had missed the deadline for filing their request and urged the court to dismiss the appeal. In actual fact, they had submitted their request shortly after becoming adults; until that moment, they had been the legal charges of the State of Israel.

The absurdity of this situation was not lost on the presiding adjudicator, Shlomi Vixen. "It would be an understatement to say that it would be difficult for me to accept the argument that the petitioners [the siblings – DD] were delinquent in filing their humanitarian request since it was filed shortly after they turned 18, and there was no reason to expect them to do so while they were still minors," he wrote. "If anything, the finger of blame should be pointed at the Israeli authorities, which did nothing during all those years and allowed the siblings to be tossed from institution to institution with no legal status."

Vixen upheld the appeal and ordered the Interior Ministry to grant Roni and Alon the status they had been seeking – temporary residency. Their case would be reviewed in two years, at which time they could be granted full citizenship.

The case of Roni and Alon is especially troubling since the siblings are also stateless. At the same time, Yaffe stressed that the Welfare Ministry's refusal to become involved in resolving such cases could also have a detrimental effect on minors who could, at least theoretically, be eligible for citizenship in another country.

"This is not a case of children of foreign parents who were born in Israel and might someday be able to move to another country. They have no other place in the world but Israel", says attorney Dana Yaffe

"Minors who could ostensibly be entitled to citizenship in another country often have absolutely no connection to that country," she explains. "They are minors who are in Israel through no fault of their own; either they were brought here as babies or were born here. The chances that they will be able to obtain the status they are entitled to in another country are slim. They do not know anybody there; they were born here. And even if we assume that the minor in question could obtain citizenship there, we still have to ask ourselves whether this is the moral decision or even a decision that safeguards that minor's rights – simply dropping them into a country that they do not know, often after 16 years of living in Israel."

Roni hopes to be granted Israeli citizenship so she can pursue her dream of serving in the Israel Defense Force. "I wanted to join up, and I looked into the possibility of volunteering, but I couldn't because I am not a citizen of the country," she says. "It was terribly hard for me because, all through high school, army service is the only thing that the kids talk about and prepare for. I wanted to be a combat unit commander and found it hard to accept that everyone would be going into the army while I would miss out. Now that I have an A5 visa [temporary resident's permit – DD], I can ask to be fast-tracked for citizenship, and we are busy writing letters to the state so that I can join the army."

Roni adds that she would like to be a commander or even join an officer's course. If Israeli bureaucracy prevents her from enlisting, she says, "I'll probably look for a normal job and get my life started properly."

The Interior Ministry declined to comment on this article.

Yonatan's story

"What did you expect? That he wouldn't descend into a life of crime?"

Yonatan (not his real name) was born in Egypt to a mother who was migrating from Africa to Israel. His mother, who was by all accounts an alcoholic, managed to reach Israeli territory but abandoned him outside the welfare department of a southern Israeli town when he was just five years old. Since then, for the past 15 years, he has been in various state-run facilities. Much like Roni and Alon, the state provided Yonatan with a foster family and boarding schools – but never bothered to resolve the issue of his long-term status in Israel.

Once he turned 18 and became a legal adult, Yonatan turned to the Refugee Rights Clinic at Tel Aviv University, which helped him obtain a student visa. This did not improve his situation by much, and he was unable to obtain an Israeli identity card. In the meantime, without any support network, Yonatan's circumstances deteriorated. He failed to turn up to an appointment to renew his visa, which was revoked. Eventually, around a year ago, he was arrested on suspicion of robbery.

Yonatan pled guilty and was convicted as part of a plea deal. Very unusually, the prosecution agreed that he would be sent for rehabilitation and therapy rather than spend time behind bars. The problems began, however, when it became apparent that Yonatan was statusless in Israel and the Welfare Ministry was unable to fund his treatment. There were also problems with his health insurance. Yonatan turned to the Interior Ministry's Humanitarian Committee, which, in addition to bureaucratic paperwork, asked him to write a personal letter.

"I have tears in my eyes as I am writing this," Yonatan wrote to the committee. "I grew up here. Despite my personal story, I grew up loving this country … I feel connected to the culture here, I only speak one language – Hebrew … I am proud to have been raised on the Jewish holidays and Israeli children's songs. I studied in Israeli schools and institutions. I grew up with Israeli friends, but there is one thing that pains me. I define myself as Israeli, but, thus far, the state has abandoned me.

"I may not have been born here, but I want my children to be born here. This is the center of my life. I want the opportunity to create here and to get closer to my identity. I want to be Jewish, to be converted by the rabbinate – and without your help, I will not be able to do this … I want to contribute and show my gratitude to this country, notwithstanding the uncharacteristic incident I was involved in, and I have already paid a very heavy price for that indiscretion.

"Until a year ago, I was a person who had ambitions, but then my visa also expired. And how can I afford to waste a day's work, because then I wouldn't have anything to eat at night, for a visa that either way doesn't allow me to work legally? It is true that I committed a serious crime, and not everyone would understand why I did it. But my answer is that I wanted to survive."

In the past few days, Yonatan's attorney, Tomer Ben Hamo from the Public Defender's Office, was informed by the Interior Ministry that it had agreed, for humanitarian reasons, to grant Yonatan permanent residency status – which would allow him to join a rehabilitation course.

"Yonatan is nobody's child," Ben Hamo told Shomrim after the decision was announced. "Nobody is responsible for him; nobody is even aware of his existence, and nobody wants to be accountable for this hot potato. He was moved from institute to institute, and when he turned 18 and one day, it was over. No more responsibility. What did they expect would happen? Did they really think that he would not descend into crime? I got the long-awaited announcement just a minute ago, and now I am just keeping my fingers crossed that they'll be able to help this kid and rehabilitate him; to give him the tools to survive in this world without anyone to support him – and, most importantly, so that he doesn't get into any more trouble."