The North is Stuck in October

Schools in the Upper Galilee are on the brink of halting education services, businesses are shuttering, and a significant portion of the population is contemplating permanent departure. In northern Israel, residents have been left neglected and overlooked since October 7. "Does Someone Have to Set Themselves on Fire for the Decision-Makers to Understand the Depth of the Crisis?". A Shomrim investigation, also featured in Mako.

Schools in the Upper Galilee are on the brink of halting education services, businesses are shuttering, and a significant portion of the population is contemplating permanent departure. In northern Israel, residents have been left neglected and overlooked since October 7. "Does Someone Have to Set Themselves on Fire for the Decision-Makers to Understand the Depth of the Crisis?". A Shomrim investigation, also featured in Mako.

Schools in the Upper Galilee are on the brink of halting education services, businesses are shuttering, and a significant portion of the population is contemplating permanent departure. In northern Israel, residents have been left neglected and overlooked since October 7. "Does Someone Have to Set Themselves on Fire for the Decision-Makers to Understand the Depth of the Crisis?". A Shomrim investigation, also featured in Mako.

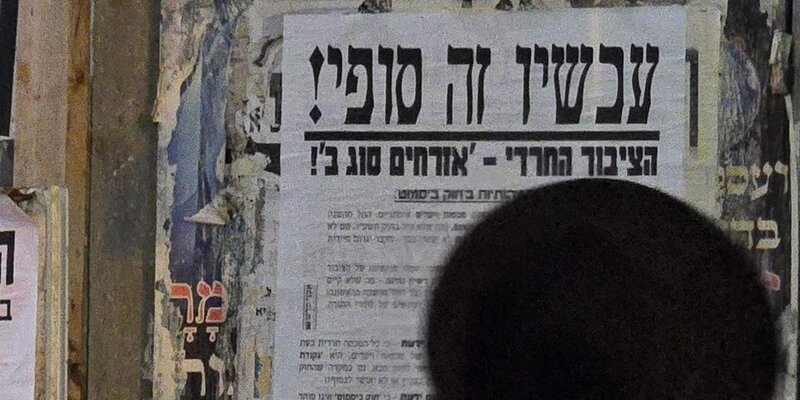

Residents from the north are taking the initiative into their own hands. Photo: Shlomi Yosef

Shuki Sadeh

March 21, 2024

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

Israelis will never forget the utter sense of shock that paralyzed their government in the first weeks after the October 7 attacks – or the helplessness of feeling that they had no one to turn to at the moment of truth. The country’s executive branch collapsed and the vacuum was filled by civil-society organizations. Now, almost six months later, this is a timely reminder; while Israelis from the center of the country have resumed some kind of routine – albeit in the shadow of the war – and residents of southern Israel have received some assistance from Tkuma, a state-agency leading the rehabilitation of the Gaza-area communities, no such solution has been found for Israelis in the north. The Upper Galilee has been deserted since the conflict erupted and its exhausted and frustrated residents have moved to other parts of the country. “We’ve got nothing. We have been left alone,” says Moran Brustin, the community coordinator on Kibbutz HaGoshrim (located 3 miles east to Kiryat Shmona, and less than 9 miles from the northern border). “We’re not getting any support from the state at all and the ministries are just squabbling amongst themselves. No one is talking to us. Some of the people who rent houses here have simply brought moving trucks and gone south. Everything is falling apart”.

As the months pass, there are more and more examples of northerners suffering extreme personal crises – from separations and divorce to career-threatening problems at work. A recent survey of residents of the eastern Galilee found that 45 percent of respondents stated that they had not yet decided whether they would move back to the north or stated that they have no intention of doing so. “There are tens of thousands of citizens who, since January 2024, are completely alone,” according to Giora Salz, head of the Upper Galilee Regional Council. “There are many issues on the table: compensation for loss of income, unpaid leave, exemption from municipal property taxes. There is a sense that there is no one to talk to. We have been left ‘home alone’ and I simply cannot understand it. Does someone have to set themselves on fire for the decision-makers to understand the depth of the crisis?”

The sense of frustration is exacerbated when northerners look southward toward the Western Negev, where the Israeli government has proven that it can do things differently. Just two weeks after the October 7 attack, the cabinet passed a resolution establishing the Tkuma Administration and then allocated 18 billion shekels (about $5 billion, including the cost of evacuating residents from the region) for a five-year plan to rebuild the Gaza envelope. Authorities managed to get Tkuma up and running relatively quickly and residents of communities adjacent to the Gaza border had a functional address in the government. Given the circumstances, it’s only natural that there are also problems, disagreements and complaints – but at least there is someone to talk to.

Within five months of its establishment, Tkuma had already come up with a plan – albeit a draft for now – for rebuilding the Gaza envelope communities over the next five years. The plan includes massive investment in rebuilding the communities and their infrastructure, as well as financial incentives to attract new residents. “In the south, the government set up an administration to handle various matters. We do not have anything of this kind and we have to chase after each ministry,” says Sorel Hershkovitz, community manager on Kibbutz Misgav Am. “The Defense Ministry demands a daily count of the number of soldiers stationed on the kibbutz, because that is how they calculate how much compensation we get. Why is it up to me to report to them? They know exactly how many soldiers are stationed, but if I miscalculate and say there were fewer, they will pay less compensation. They seem to have forgotten that the government should serve us, not the other way round.”

“The equation is simple: if more people had been killed in the north, the Israeli government would have set up Tkuma for us,” insists Eitan Davidi, chair of the residents’ committee on Moshav Margaliot (Located along the border with Lebanon, under the jurisdiction of Mevo'ot HaHermon Regional Council). “That’s what it looks like from here. I’ll give you an example: people in Margaliot rely heavily on generators because there are frequent power outages here. No contractor is willing to come here. We turned to the IDF’s Northern Command and they referred us to the Northern Horizon directorate, which took three weeks to find someone willing to come. That’s not what I call looking after citizens. In the end, I found a way to get diesel. But why should I have to deal with these things? The State of Israel should be responsible for getting diesel to the north of the country, like it does in Gaza.”

"The moment that the government decides to launch a war of attrition, it must also take into account the civilian significance. For every month that we do not return to the Galilee, 10 percent of the residents and the businesses will never come back", says Erel Margalit, executive chairman of the Jerusalem Venture Partners capital firm.

The Budget: So What if Netanyahu Gave Instructions?

The Defense Ministry established the Northern Horizon directorate in December 2023. It works with local authorities primarily on various military issues, such as soldiers’ lodgings on kibbutzim and moshavim, coordination with the communities’ security units and fortifying buildings. Two months earlier, the government decided to set up a civilian control center within the Finance Ministry, which was supposed to deal with a wide range of war-related issues across the country, apart from the Gaza envelope, for which Tkuma was established. Since then, however, the powers and goals of this body were ambiguous and residents of the north, who were most in need of the state’s assistance, barely felt its existence. In late January, less than three months after he was appointed to head the civilian control center, Tal Basechess, the former CEO of the Israel Association of Community Centers, stepped down.

Just after Basechess’ resignation, the cabinet held a meeting in the village of Korazim (5 miles north of the Sea of Galilee), specifically to discuss the situation in the north. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu instructed officials to draw up a detailed plan to help the region within 10 days. Since then, it seems, nothing has happened.

Shomrim looked into the matter and discovered that Interior Minister director general Ronen Peretz did indeed prepare a draft resolution for ministers, but it was never brought to the cabinet for discussion. Among the proposals was to allocate 3.5 billion shekels (almost $1 billion) over the next five years exclusively for investment in the north, separate from the funding needed to evacuate residents or the other day-to-day expenses created by the war. This never happened, however, in part due to disagreements over authority. Heads of local authorities in the north wanted Peretz to be the project manager responsible for making the plan happen, but Finance Minister Betzalel Smotrich wanted to appoint his party colleague, Settlements Minister Orit Strock, to oversee the project in rural areas. In other words, in the regional councils. Similarly, there were several senior civil servants who opposed Strock’s appointment, saying that one person should manage the entire project – rural and urban areas alike.

“Either way, the draft resolution exists, at least in its preliminary stage, but it is not being brought before the cabinet for approval. The finance minister is delaying it and every wasted moment is a shame,” says Gabi Ne’eman, head of the Shlomi Regional Council, in the western Galilee. “The government isn’t talking to us; ministers do not come to the area. Smotrich wants Strock to run the project, but it is a project that is primarily budgetary in nature, in which funding is supposed to be pooled. We simply cannot see how Strock can be the project manager for this''. In mid-March, the government also approved the state budget for 2024. Did it include funding for the government projects designed to rebuild the north or for a special government resolution on the north, as Netanyahu promised it would? The answer is no. Everything was stalled – as the official minutes show.

At a meeting of the Knesset’s Special Committee on the Negev and the Galilee, which took place on February 19, committee chair MK Michael Biton (National Union) asked the deputy head of budgetary division at the treasury, Yedidya Greenwald, “How many billions [of shekels] are you setting aside for civilian economic needs in the north?”

In response, Greenwald said that “in the framework of the current budget, we have set aside very significant budgets for the north, and we will provide more when needed,”

Biton did not relent and asked: “How much? Not in words. How much?”

Again, Greenwald provided a vague answer. “The framework has not yet been finalized because the needs have not yet been fully finalized. As I said, every government ministry has allocated hundreds of millions of shekels for the upcoming year alone. The framework, as the chairman said, is not clear yet. We still don’t know what needs will arise.”

Biton continued: “What sum will appear when you bring the 2024 budget to the Finance Committee?”

“No sum will appear,” Greenwald replied.

Two weeks later, during a Knesset discussion on the budget, Biton told lawmakers, “we will either expand the role of the Tkuma Administration in the south and just add the word ‘north,’ or we will set up a Tkuma North. In the meantime, we appear to be a sleeping administration; we are dozing instead of helping the civilian economy for residents of the north.”

.jpeg)

Gabi Ne’eman, head of the Shlomi Regional Council: “The government isn’t talking to us; ministers do not come to the area. Smotrich wants Strock to run the project, but it is a project that is primarily budgetary in nature, in which funding is supposed to be pooled. We simply cannot see how Strock can be the project manager for this''.

Education: ‘On September 1, They’ll Study on the Back Slope, Not the Font One’

In an effort to waken the decision-makers from their slumbers, the Conflict Zone Forum, which represents more than 20 communities in northern Israel, gave the government a deadline, saying that they expect schools in the north to return to studies by September 1 – the traditional start date. “As far as we are concerned,” says Salz. “The plan is clear and the next school year must start on the same date that it has started in previous years. For that to happen, the conflict on the northern border has to end by late June or early July. Either with an agreement or after more fighting.”

It is no coincidence that September 1 was chosen as the target date for a return to routine in the north. The education situation is especially acute for residents and their children; since the start of the war, the northern branch of the Education Ministry has been busy trying to find schools for children evacuated from the north, while, at the same time, setting up new schools for those who have relocated to other areas. And they not only have to look out for the welfare of the children, but also of evacuated teachers. In total, of the 50,000 children that the Education Ministry looks after in northern Israel, more than 16,000 have been evacuated – but only 6,700 of them to regions located further south. One new school was set up in the Poria region, serving children evacuated from communities close to the Sea of Galilee.

How does it work in practice? Within the area of the Upper Galilee Regional Council, for example, there are four schools attended by children from neighboring councils. Since these are regional schools, where there are children from communities that were evacuated and those from communities that were not, entire year groups of children have been relocated to different schools. At the regional school in Kibbutz Kfar Blum, who wasn’t evacuated but is located at the north of Hula Valley (4 miles southeast of evacuated Kiryat Shmona) the Home Front Command has imposed limitations on the number of students, there are some children who study in their regular classes, but others from different classes in the same year group who go to school in Tiberias. In other cases, schools use a two-shift system. When lessons end at 1 P.M. at the school in Hatzor Haglilit, for example, highschoolers from Har V’Guy, located in evacuated Kibbutz Dafna, arrive and settle down for their studies. Likewise, some 600 students from Kfar Blum travel to Kibbutz Ayelet Hashahar (22 miles south of Kiryat Shmona) where they have the ‘second shift’ in the school.

This lack of certainty over the next school year is the main reason so many families are considering leaving the area. “Some parents say to themselves: If we end the current school year without knowing what’s happening next year, we’re better off moving south now, so that we will have a degree of certainty about next year,” says Brustin from Kibbutz Hagoshrim.

Notwithstanding the demand of the Conflict Zone Forum to start the next school year on time, there are moves afoot which could put paid to any such plans because of local and national politics. Head of the Mevo’ot Hahermon Regional Council, Beni Ben Muvhar, wants to expand the existing school in the Korazim area, so that next year it will be able to take in students from schools located to the north, in the area of the Upper Galilee Regional Council. Ben Muvhar has already received budgetary permission for the move and is planning on erecting 20 mobile structures on the land.

“The plan was for a growing school at Korazim for seventh- and eighth-grade students, but we can absorb there another school that can serve as an alternative to the school on Kfar Blum, the Einot school on Kibbutz Amir or the Har V’Guy high school on Kibbutz Dafna,” says Ben Muvhar. “We can take the three of them and establish a new school at Korazim – it all depends on the Education Ministry. If the situation changes and by September 1 things go back to normal, we will still be able to use the classrooms that were earmarked for evacuees. At the moment, I am preparing for September 1, when the students will study in the back slope and not the front slope.”

There are some northerners who are very much opposed to this proposal. Apart from the fact that it threatens the uniform position that the Conflict Zone Forum wants to present to the decision-makers, it is also a de facto admission that the state has given up on the north and that it is incapable of providing security for students in the Upper Galilee. In this context, one senior local government official told Shomrim that, “the idea of a school at Korazim is something that started even before the war, when Ben Muvhar wanted permission to set up a large school. Sometimes, an event like the war can move projects forward even more quickly. But a school like Har V’Guy won’t study there. On September 1, everybody will be going back to exactly the same school.”

The Education Ministry, for its part, is preparing for any one of three eventualities: a return to normal on September 1; a partial return to normal on September 1 in some communities, excluding those directly on the border; and extending the current situation. According to Dr. Orna Simhon, director of the Education Ministry’s North District, if the new classrooms on Korazim are ready within six weeks, then students from Kfar Blum, who currently study on the second shift at Kibbutz Ayelet Hashahar, will start studying there even before the end of the current school year. If the current situation is extended, they will also start the next school year there. The solution for students currently attending Har V’Guy – if necessary – will be to renovate structures on the Tzahar Industrial Park near Rosh Pina.

“Given the uncertainty and ambiguity, we have to prepare for all three scenarios,” Simhon told Shomrim. “We have to see which parents have moved to a new apartment, which parents do not want their children to study in remote locations – but still want to keep living where they are now. Maybe there are teachers who have fallen in love with someone in Tel Aviv and don’t want to come back to Kiryat Shmona. Even now, there are some teachers who are telling us that they want to sell their home in Shlomi and move to Nahariya, which was not evacuated and where, relatively speaking, life goes on as normal. This is an extremely complex situation in which the Education Ministry is trying to look after every single family.”

MK Biton: "We will either expand the role of the Tkuma Administration in the south and just add the word ‘north,’ or we will set up a Tkuma North. In the meantime, we appear to be a sleeping administration; we are dozing instead of helping the civilian economy for residents of the north.”

.jpeg)

The Future: ‘Every Month Away Means Another 10 Percent Won’t Come Back At All’

In the absence of any governmental initiative, the vacuum is being filled by the local authorities, which are trying to provide answers for all residents. They do not always succeed, however, and they also do not have the free time to be thinking about the long-term future. Like in the case of the civil-society initiatives that were launched in the aftermath of the October 7 attacks, northerns are coming to understand that if they do not take matters into their own hands, nothing will happen.

Against this backdrop, four residents of the eastern Galilee – Shimrit Assor, Liat Cohen-Raviv, Ivri Asulin and Amir Edry – recently came together to launch a new initiative called Matzpinim. One Friday in mid-March, they held a meeting at a café in Rosh Pina to discuss their long-term plans for the region. Assor says that around 40 locals showed up for the meeting, where they discussed a number of issues, having surveyed local people to find out what they most wanted to see changed: commerce, education and health, with the emphasis on mental health, topped the list. Apart from that, they also discussed issues such as the tension between the urban areas and the rural spaces, which has existed in the region for many years.

“First of all, we agreed not to talk about what has already been agreed with the government: establishing a university and a new hospital in the Galilee. But there are a lot of other issues,” Assor says. “For example, we would like for every school to have its unique characteristics – science and computers, arts, theater, music and cinema. On the issue of mental health, we talked about the need for preventative actions and how we can treat people so that they can avoid or lessen the trauma. We also spoke about the need to increase wages for employees and to create incentives to attract businesses to the region. When it comes to education, it is obvious to everyone that we need more teachers here and we see similar projects currently being drawn up in the south.”

People in the north see how Tkuma is planning on setting up the southern branch of the Wingate Institute in the Gaza envelope, as well as two new medical centers and incentives for people who decide to move to the region – and they want similar plans for the north. “We are an organization of action, not protest,” Assor insists. “Our goal is to come up with ideas so that the heads of our local authorities and the government can use them. We want to make the residents’ voices heard.”

The question is, however, whether the immediate future will overwhelm the region before any of that happens. “Around 95 percent of the businesses that were established in the region in recent years have closed down or moved to Caesarea, Yokne’am and Tel Aviv,” says Salz. “Factories have simply moved to other places. My big concern is what will happen with overseas investors; they could leave and never come back.”

A few years ago, former Knesset member Erel Margalit, who is executive chairman of the Jerusalem Venture Partners capital firm, set up a food-tech company in the Upper Galilee, which operates from a large building opposite the central bus station in Kiryat Shmona. He is currently keeping a worried eye not only on his own initiative, but on all the start-ups in the region. “Before the war, there were 104 very serious start-ups, most of them in the field of food-tech,” he says. “Since the terrible decision to evacuate residents, the situation has deteriorated greatly. Almost everyone has moved somewhere else. A month ago, we held a conference for 75 start-ups in a large café at Mahanaim Junction; we brought along 15 commercial funds to see how they could help. We even got Dror Bin, the head of the Israel Innovation Authority and Bank of Israel governor Amir Yaron to come along. Yaron came to give directions to the banks.

“Bin drew up a very good plan for start-ups across the country, but most of the elements are not relevant for the Galilee. The state must allocate large sums of money through the Innovation Authority, which will provide the start-ups with something like six to nine months of operational costs, because many of them are not yet well enough established. The same is true of other businesses: we have to compensate the ice-cream seller and the baker from downtown Kiryat Shmona for their loss of income and not for their expenses.”

In summary, Margalit says “I am not coming from a place of criticism toward the government for deciding not to launch an all-out war in the north. But the moment that the government decides to launch a war of attrition, it must also take into account the civilian significance. For every month that we do not return to the Galilee, 10 percent of the residents and the businesses will never come back. But there is no project manager for the north, there’s no special budget and there is nobody overseeing the whole thing. Every day that passes, we’re losing the north.”

Responses

The Ministry of Settlements and National Missions, headed by Orit Strock: “The prime minister instructed the director general of the Prime Minister's Office to draw up a government resolution about the north. The Ministry of Settlements and National Missions is assisting the director general of the PMO to advance this resolution and is providing its services and expertise so that the resolution will lead the rehabilitation and expansion of settlement in the north. We are unaware of any other publication on the subject.”

The Defense Ministry: “When the war broke out and thousands of reservists were mobilized, it was discovered that a large proportion of IDF soldiers were billeted in civilian facilities. Due to the current situation, the Defense Ministry has implemented a system whereby civilians who house soldiers in their facilities can apply for reimbursement for water and electricity. This is done in accordance with criteria that were determined in advance.

“Civilians should submit requests to the Defense Minister, in which they state how many soldiers are billeted in their facilities. This statement is then verified by relevant officials from the defense establishment and is the basis for reimbursement. If the civilian is not able to gauge how many soldiers are billeted, the reimbursement is based on figures from the relevant official.”

Shomrim also asked the Finance Ministry for a statement but was told to contact the Prime Minister's Office instead. The PMO did not submit a response by press time.