The Ultra-Orthodox Draft Law is Tearing The National-Religious Camp Apart

A cartoon depicting a yeshiva student sitting on a stretcher alongside an injured soldier, telling him that ‘Torah study is dedicated to your recovery,’ published recently in the national-religious camp’s flagship newspaper, gave voice to the fury that has built up toward ultra-Orthodox society since October 7, given the high number of knitted skullcap-wearing soldiers killed in combat. Is this the turning point that will dismantle the political alliance between the two camps? Shomrim takes a deep dive into the issue that has divided the right

A cartoon depicting a yeshiva student sitting on a stretcher alongside an injured soldier, telling him that ‘Torah study is dedicated to your recovery,’ published recently in the national-religious camp’s flagship newspaper, gave voice to the fury that has built up toward ultra-Orthodox society since October 7, given the high number of knitted skullcap-wearing soldiers killed in combat. Is this the turning point that will dismantle the political alliance between the two camps? Shomrim takes a deep dive into the issue that has divided the right

A cartoon depicting a yeshiva student sitting on a stretcher alongside an injured soldier, telling him that ‘Torah study is dedicated to your recovery,’ published recently in the national-religious camp’s flagship newspaper, gave voice to the fury that has built up toward ultra-Orthodox society since October 7, given the high number of knitted skullcap-wearing soldiers killed in combat. Is this the turning point that will dismantle the political alliance between the two camps? Shomrim takes a deep dive into the issue that has divided the right

Ultra-Orthodox youth look at the flag parade of the national religious community this month in Jerusalem. Photo: Reuters

Chen Shalita

June 18, 2024

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

“All these years, whenever anyone asked me if I felt closer to the ultra-Orthodox or the secular, I positioned myself closer to the ultra-Orthodox,” says Ido Pizam, a 60-year-old attorney from Hoshaya, a national-religious community in northern Israel. “When they talked about a small and professional army. I even thought, ‘Wow, that’s a good idea; not only will we not have to fight with the ultra-Orthodox, but my son, who has served for so many years, will get a normal salary.’ On October 7, I crossed the line into the secular camp. My son has been in Gaza for eight months. Whenever there’s a knock at the door, even at four o’clock in the afternoon, my heart sinks. People close to me know that they shouldn’t knock on our door unless they call first to tell us they are coming over, because it terrifies me. The ultra-Orthodox are not terrified by a knock at the door or rumors about a tragedy with many fatalities. They don’t have to live with such worries. ”

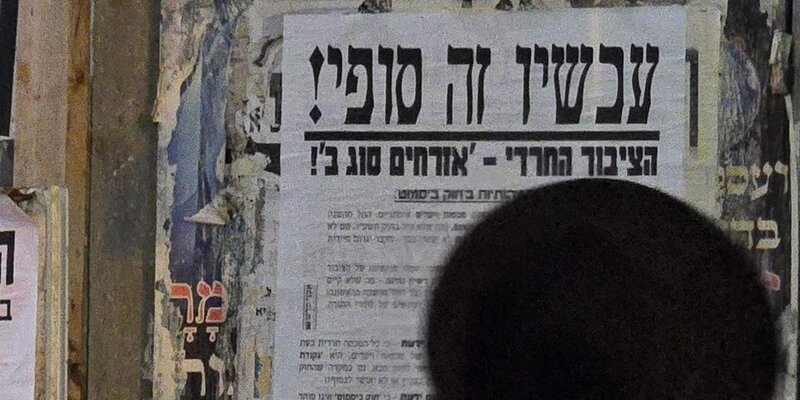

Pizam lists the names of the fatalities and injured from Hoshaya and among his extended family. “We wake up with it in the morning and go to sleep with it at night. For us, it’s not just an item on the news. All these years, we bowed our heads to the Torah study of the ultra-Orthodox. They cling on to the Torah and we combine – but that’s it. It’s over. After October 7, we are no longer willing to bear it. I can see it in the parlor meetings. The anger is sky high.”

Senior rabbis from the religious-Zionist camp have called on the ultra-Orthodox to join the IDF. Some of them subsequently retracted. Is it possible that their frustration will be limited to merely letting off steam?

“You don’t understand how dramatic the very existence of the letter is. Rabbis with knitted kippah banging their fists on the table and telling them that Torah study alone cannot protect Israel and that it is not moral to continue this way. Nothing like this has ever happened. We have to get the ultra-Orthodox out of the position they are currently in. They can establish their own battalions with their own crazy rules – but they have to be drafted. Even though I am a rightist and a right-wing government is important to me, I would prefer a unity government with the center-left. The main thing is resolving the ultra-Orthodox draft problem once and for all.”

While many members of the national-religious community share this anger, not all of them, like Pizam, are willing to pay the price of the collapse of the right-wing government. “If the price of going head-to-head with the ultra-Orthodox is that Yair Lapid becomes prime minister, I prefer to cut corners when it comes to the issue of the draft,” says one skullcap-wearing member of a rapid response team from a community in southern Israel. So, even though I also think that it’s no longer justified that they do not serve in the IDF, a left-wing government is not a price that I am willing to pay.”

Earlier this week, the Knesset’s Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee began discussing the ultra-Orthodox recruitment law, ahead of its presentation to the Knesset for its second and third readings. The legislation was originally submitted during the time of the so-called “government of change” as a temporary measure and earlier this month the entire coalition banded together to ensure that the Rule of Continuity – allowing the bill to move from the previous Knesset to the current one – would apply. The law sets low draft levels for the ultra-Orthodox community and lowers the current age of exemption from mandatory service for yeshiva students. Attorney General Gali Baharav Miara said that the law should not be advanced since it is irrelevant to the current needs of the IDF after October 7 and ignores the threat of war on several fronts that has become a realistic scenario.

How far will the national-religious community be willing to go in order for the ultra-Orthodox to be drafted? Will they press their representatives in the Knesset to bring down the government if draft targets are not changed? An analysis of the changes that this community’s worldview has undergone since October 7 shows that the issue of ultra-Orthodox service in the IDF is by far the most important issue. One example of this is the cartoon that was published over the weekend by Shay Charka, a religious cartoonist who publishes in the right-leaning Makor Rishon newspaper. His cartoon depicts soldiers carrying an injured comrade on a stretcher. Sitting on the injured soldier is a yeshiva student pouring over a holy book. “Don’t worry,” the student tells the soldiers. “My studies are dedicated to his recovery and your success.” The cartoon accurately reflected the anger among the national-religious camp, created a widespread public discussion and embarrassed the knitted skullcap-wearing Knesset members who voted in favor of the law.

More than half of the right wants an ultra-Orthodox draft

Shlomit Ravitsky Tur-Paz, the director of the Center for Shared Society and head of the Religion and State Program at the Israel Democracy Institute, has also noticed this growing impatience. A recent survey she conducted into the views of the Jewish population of Israel on the issue of ultra-Orthodox recruitment found that 60 percent of people who voted for Habayit Hayehudi in the last election and 52 percent of those who voted for Religious Zionism or Likud are in favor of ultra-Orthodox service in the army. “With the exception of the Haredi-national-religious camp,” Ravitsky Tur-Paz tells Shomrim, “the entire national-religious center – and, of course, the liberal fringes – has moved toward a position that endangers the future of the coalition over the issue of the ultra-Orthodox draft. They are angry with their political leaders, whose loyalty to the ultra-Orthodox overcame their loyalty to their own constituents, who are paying a heavy price in this war.”

"There is no question that the national-religious community’s acceptance of the ultra-Orthodox public when it comes to the gap between rights and duties, and to discrimination between them, is over."

Indeed, the political leadership of the Religious Zionism party originally opted not to deal with the issue at all and then decided to placate its voters with empty comments. It did not, however, exert the kind of pressure that it has in the past on issues that it genuinely cares about. Party leader Betzalel Smotrich, who comes from the Haredi-national-religious camp, has spoken about the need for change – through dialogue, of course – but continued to vote along with the rest of the coalition. He vented the cumulative rage that has been directed at him on the IDF chief of staff at a cabinet meeting this week.

“Don’t talk about the draft law,” Smotrich angrily told Herzl Halevi. “You’re interfering in a political issue.” In response, Halevi said that “the IDF needs it for security reasons. Take responsibility. I know that’s not a common word around here.” Yehoda Vald, the CEO of the party, wrote on social media that “Aryeh Deri should not come to any more meetings of the war cabinet until he takes genuine measures to bring about significant ultra-Orthodox recruitment. Morally and ethically, he cannot send me and my friends to the battlefield … Enough is enough.” In a subsequent interview with Arutz 7, however, he added that there must be no forced enlistment and that it is important to safeguard the stability of the coalition.

This duality has political ramifications. The liberal camp, which is worth approximately one and a half seats in the Knesset for the national-religious parties, is not consequential for the parties that make up the coalition – not even those liberal ones which express moderate right-wing views. The Religious-Zionist mainstream is a vastly different matter; since they provide around half of the camp’s seats in parliament, their support for a different national-religious or right-wing party that would take a stand on the issue of the ultra-Orthodox draft, would shake up the entire electoral map.

“A lot depends on whether a new party is established and what will be top of its agenda when the time comes,” Ravitsky Tur-Paz believes. “But there is no question that the national-religious community’s acceptance of the ultra-Orthodox public when it comes to the gap between rights and duties, and to discrimination between them, is over. That was even evident in the High Court hearings. The most impatient justices, the ones who asked the most questions of the state’s representatives, were Noam Sohlberg and Yael Willner – both of whom are religious. Why? Because they come from a society in which the number of people serving in the army and in the reserves is massive and they see how their people are exhausted, being called up for long reserve duty for a second or third time – not to mention the number of fatalities and injuries among this community.”

Yair Sheleg, a research fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute and a journalist for Makor Rishon, recently published a book called “The Third Thread: A Brief History of religious Zionism.” He views ultra-Orthodox refusal to serve in the army during a time of war as a watershed moment in relations between the two communities. “Up until this current war, religious Zionism – especially its political leadership – had an alliance with the ultra-Orthodox world in the framework of a right-wing government,” he explains. “You help us keep hold of the Land of Israel and we will help you protect the yeshiva students. The war shattered that alliance, certainly among the general public, because the leadership is more cautious. The vast majority of the national-religious camp is no longer willing to support the blanket exemption that yeshiva students get. They no longer feel comfortable defending the ultra-Orthodox who refuse to join the army, as they were before the war. Even if they remain together politically for the sake of the right-wing government – like parents who do not get divorced because of the children – the enthusiasm is no longer there.”

Are there any other common denominators?

“Yes and no. There is a great deal of resentment within the religious Zionist camp toward the ultra-Orthodox, whom they accuse of taking all the positions in the religious establishment and appointing people with extremist views on issues such as women whose husbands refuse to divorce them and conversion. For many years, they let the ultra-Orthodox get away with it and let them have the final say on matters of religion and state – and now they are also fighting over the loss of statehood here. You can see it in dissatisfaction with the “Rabbis’ Law,” which empowers the rabbinical courts and the religious affairs minister, who is from Shas, to appoint rabbis, rather than the local authorities.”

Is the national-religious camp not engendering itself by breaking this alliance?

“Actually, it is coming from a place of security because the ultra-Orthodox parties can no longer play the left off against the right, even if they wanted to. The young generation of ultra-Orthodox Israelis is very right wing and, in any case, will not let the politicians join any government that is not right-wing.”

Yair Sheleg, a research fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute and a journalist for Makor Rishon: “Up until this current war, religious Zionism had an alliance with the ultra-Orthodox world in the framework of a right-wing government. You help us keep hold of the Land of Israel and we will help you protect the yeshiva students. The war shattered that alliance."

‘Three or four Knesset seats looking for a home’

Dr. Menachem Lazer, from Bar-Ilan University, is one of the most prominent scholars of national-religious society. He is less certain about how daring the knitted skullcap-wearing public will be when it comes to rocking the boat. That may explain why, in a survey he conducted in April, he went one step further by asking respondents whether they would prefer a government with the ultra-Orthodox parties – one which would not advance the draft for yeshiva students and would not seek to integrate them into society – or a left-wing government. In response, 55 percent said that they would prefer the former over the latter. Breaking that down into sectors, we see that 76 percent of the Haredi national-religious, 48 percent of the mainstream (“What used to be referred to as the silent bourgeois majority,” says Lazar) and 42 percent of the liberals would also prefer a government with the ultra-Orthodox.

“This camp is very varied in terms of religiosity, but extremely monolithic politically,” Lazar explains. “The vast majority is on the right of the spectrum politically and in terms of security – and I am also including the liberals in this. Being left-wing religiously does not mean being left-wing politically. That is why a left-wing government is a threat to them. On the other hand, the survey was conducted two months ago; the ongoing war and the ever-lengthening list of casualties could change the situation. People are upset. The letter from the rabbis was published now, not two months ago, because it takes time for things to come to a head. If I were to repeat the survey today, the outcome would be a little different.”

Smotrich’s party is hovering around the electoral threshold. Does that also reflect some dissatisfaction?

“Smotrich has a solid base of support that is worth four or five seats. That is, in fact, the Haredi national-religious, conservative powerbase of the National Union-Tkuma party.”

.jpg)

Sheleg adds: “The seats that the Religious Zionism party won at the last election were a kind of mistake. The public was furious at Bennett and Shaked, who broke their promise and joined a left-wing government with the United Arab List. Either they punished Shaked at the voting booth or they did not believe she would get past the electoral threshold. Either way, voting for Smotrich was a kind of default and now he has shrunk back to his natural size. Because he is the sector’s only party and has also adopted the name, there is a sense that the entire national-religious public supports him, which is not the case. People have switched temporarily to Gantz and are waiting to see what kind of right-wing party will emerge and whether it will be more responsible. Contrary to widespread belief, a lot of the national-religious camp’s votes go to parties outside the sector.”

Ariel Finkelstein, who has studied the knitted-skullcap community for the Israel Democracy Institute, believes that “there is a demand for a right-wing, religious approach that is not ultra-Orthodox. Even before the war, not everyone liked the direction Smotrich was heading.”

Are you referring to those people who demonstrated against judicial reform?

“In part – but there was another group, too, that did not necessarily object to the content of the reforms. They wanted the legislation to be passed with a broad consensus and from a place of unity. Smotrich comes from the fringes. He does not represent the mainstream of the national-religious camp. His religious lifestyle is also on the extremes. Compared to him, Gantz and Eisenkot offer a more conciliatory approach to the war, while some people still find it hard to forgive Bennett. Now that the issue of the ultra-Orthodox draft is also on the agenda, there will be a lot more willingness to welcome a statesman like party which is mature enough to forge alliances with the center.”

Smotrich’s media adviser did not respond to a request to interview the minister for this article. Another member of his party, MK Simcha Rothman, did have something to say on the matter. “The consistent position of our party has always been that there is no contradiction between studying Torah and fighting in the army,” he says. “I am a resident of Gush Etzion. The military section of our local cemetery has quadrupled in size since the start of the war. Military service is a mitzvah and a duty – and in this respect, nothing has changed. But what can you do when you are in a coalition and your political partners disagree with you? Do you take reality into account or do you live in your ideal world and decide to squabble over everything? Anger is not an action plan. Sometimes, reality does not square with your ideology but this is no different than other issues over which we have to reach agreements.”

Former prime minister Naftali Bennett, who has already declared that he intends to compete in the next election, wrote on social media platform X, formerly Twitter, in the aftermath of the APC disaster in Rafah, that “there is no place for a blanket exemption for an entire population. We need everyone fighting together in the war against our enemies.”

"Smotrich was a kind of default and now he has shrunk back to his natural size," says Yair Sheleg. "Because he is the sector’s only party and has also adopted the name, there is a sense that the entire national-religious public supports him, which is not the case."

‘Most of the national-religious public is pragmatic’

Let’s return to the issue of fallen IDF soldiers in the current war. Prof. Yagil Levy, an expert in civil-military relations from the Open University, has been tracking the demographic breakdown of IDF fatalities since the first Lebanon War. Data he has collated since October 7 shows that “religious soldiers make up almost 30 percent of the fatalities on all fronts, except in the West Bank. In comparison, in the Second Lebanon War, the last war in which there was such a large number of fatalities, religious soldiers made up 13 percent of the fallen. The main significant increase is the 80-percent rise in religious fatalities from the settelments in the West Bank compared to the Second Lebanon War. In 2006, they made up around 5 percent of the fallen, compared to almost 9 percent in the current war. The data is accurate as of last week, but since then there have been more fatalities, including several religious soldiers.”

The reasons for this are varied, including the establishment of more pre-military religious academies, the ethos of sacrifice with which young members of the national-religious community are inculcated and the motivation of these soldiers and their leaders to occupy key roles in the ground forces and in the senior officer class, which, according to Levy, was boosted by the disengagement from the Gaza Strip in 2005.

"The fact that we are ‘literally’ on the front line is a source of pride and great joy for us. We do not feel that way everywhere. We do not feel like we are on the front lines of the civil service, the media or the judiciary.”

“I don’t know if ‘counting kippot’ is the right definition,” says Eitan Zeliger, who runs a strategic consulting company, “but the fact that we are ‘literally’ on the front line is a source of pride and great joy for us. We do not feel that way everywhere. We do not feel like we are on the front lines of the civil service, the media or the judiciary.”

You have so many officials in senior positions in those places.

“Even if we do, we never felt as at home there as we do now in the army, where we can sense the unity. Once we were accused of polarizing the nation because of the judicial reform; after October 7, the religious public feels like it is part of the same story. I visited a national-religious community a few days ago and the number of people in uniform and carrying weapons is incredible.”

What impact will the high number of fatalities have? Will there be some families who say that, with all due respect to the ethos, we’re not willing to make this sacrifice? “No chance,” says Prof. Asher Cohen, a researcher into religious Zionism from Bar-Ilan University. “The whole education system in religious Zionist society is built on collective contribution and meaningful service in the IDF. This also manifests itself in a crazy phenomenon in our ranks of donating a kidney. Did you know that there are more kidney donors in one small hilltop settlement than in any other community in Israel? That’s why you won’t find anyone talking about a change of direction in any of the streams of religious Zionism, from the most liberal to the ultra-Orthodox. You can scour every religious Zionist newspaper and I promise you that you won’t find a single article saying that we need to rethink or that we have already sacrificed too much.”

"War moves people to the right, to more hawkish positions. And October 7 was such a massive event that it will shift entire processes."

Finkelstein also does not expect the families of fallen soldiers to express any second thoughts. “That’s leftist wishful thinking,” he says. “War moves people to the right, to more hawkish positions. And October 7 was such a massive event that it will shift entire processes. After the Yom Kippur War, the Gush Emunim movement emerged. You’ll note that it didn’t happen after 1967, when we captured the territories. There were hardly any settlements before the Yom Kippur War. And, ironically, after the schism of that war, and even though there was no combat in Judea and Samaria in that conflict, it happened. Here, too, things will happen in our camp that it is still too soon to predict.”

Sheleg, in contrast, does not rule out the possibility that the considerable number of fatalities will shake the national-religious community and move it to a less militant place. “The Kibbutz Movement paid an extremely high price in the Yom Kippur War,” he says. “In that war, 18 percent of the fatalities were kibbutzniks, while they made up just 3 percent of the total population. That blow created a schism and a reckoning among the kibbutzniks and it will be interesting to see if something similar happens with the national-religious community. There are no indications of it just yet, but these processes take time.”

In the meantime, the idea of resettling the Gaza Strip as an act of revenge and to bolster security is starting to catch on.

“Most of the national-religious public is pragmatic. Even those who have no ideological opposition to settling Gaza understand that it would be crazy to do so now, especially given that Israel is also fighting to prove the legitimacy of its war. Even Smotrich isn’t making it one of his demands. Everyone understands that this war is a critical mission. Anything that could derail it has to wait.”