Growing Up Without Knowing You Can Be Abused: ‘I Didn’t Understand What We Wanted and Then He Started Touching Me’

Around 400,000 boys and girls are enrolled in Israel’s ultra-Orthodox education system, where there is no sex education of any kind and it does not look like there ever will be. This leads to sexual abuse and coverups, problems in adult relationships, low self-esteem and many other issues. Two young men and one young woman, who grew up in the ultra-Orthodox community, open up to Shomrim about how this has upended their lives

Around 400,000 boys and girls are enrolled in Israel’s ultra-Orthodox education system, where there is no sex education of any kind and it does not look like there ever will be. This leads to sexual abuse and coverups, problems in adult relationships, low self-esteem and many other issues. Two young men and one young woman, who grew up in the ultra-Orthodox community, open up to Shomrim about how this has upended their lives

Around 400,000 boys and girls are enrolled in Israel’s ultra-Orthodox education system, where there is no sex education of any kind and it does not look like there ever will be. This leads to sexual abuse and coverups, problems in adult relationships, low self-esteem and many other issues. Two young men and one young woman, who grew up in the ultra-Orthodox community, open up to Shomrim about how this has upended their lives

Illustration: Shutterstock

Lir Spiriton

August 27, 2024

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

“There’s one case that I remember very well. There were two families coming back from the wedding of a cousin. The last bus from Jerusalem to Bnei Brak. It was late at night and dark; most people were already asleep. He sat down next to me on one of the seats at the back of the bus and told me not to say anything, not to tell anyone. I didn’t understand what he wanted and then, suddenly, he started touching me and then touching himself. And that’s it. I don’t want to go into further detail.”

David, a young man in his mid-20s, grew up in Bnei Brak in a very well-known institution. He stops and it is hard for him to continue. The abuser he is talking about is his uncle, whom he describes as “a respected Hassid, with a long, white beard and an important job.” That assault on the bus back from Jerusalem was not the only incident, David says.

“I remember one Shabbat morning he took me into the restroom and locked the door. It’s hard for me to talk about it. I suffer from crazy blackouts. Hang on.” He stops again, takes deep breaths and then continues. It is clearly important for him to do so. He says that, when he was around 11 years old, he went alone to the mikveh, the ritual baths, from when he continued to the Talmud Torah where he studied, utterly unaware of what just happened. He goes on to talk about the many sexual assaults that children in the ultra-Orthodox community suffer, about the total lack of awareness – not only of the child victims, but also of their parents – of the severity of these incidents and the lack of enforcement. “People who ought to be in prison probably will never be brought to justice. The abuser apparently knows that the police will not be brought in. My father, for example, would not turn in his own brother even if he knew what he had done.”

David was the victim of severe sexual abuse and his story – like those of the people Shomrim interviewed for this article – brings to the surface one of the most fundamental problem when it comes to sexual abuse, marital relations and body image in ultra-Orthodox society: a lack of knowledge and understanding stemming from the absence of any kind of education on the subject, formal or otherwise. As far as the ultra-Orthodox education system is concerned, the issue simply does not exist and is not addressed, not in terms of sexual safety, puberty or general sex education. This is not a case of a gray area in which young people acquire this knowledge through different means; even at a more mature age this is not an option. Rather, hundreds of thousands of children are raised without knowing what is happening to their bodies and without even imagining that they could be abused. And as if that were not enough, these children are also exposed to problematic messaging when it comes to their sexuality and the sexual relationships they will have with others when they reach maturity.

The ramifications are countless and branch out into many and varied areas. So much so, in fact, that it is almost impossible to properly gage the damage, from sexual assault to coverups of such attacks, with the victim and their family not speaking out, to emotional issues and rage and physical and emotional attacks on women who find themselves and their partner without adequate preparation on their wedding night.

.jpeg)

‘There is a massive lack of knowledge’

Israel’s state-run education system has several sex education programs for children and youngsters. In elementary school, educators focus on the issue of safety – the importance of personal space, the ability to recognize situations of potential abuse and how to reach out to a person of authority if the need arises. In the sixth grade, teachers also talk about the biological and cultural changes that occur during puberty and in middle school the focus switches to relationships, recognizing red flags and so on. The Education Ministry says that these programs have been adapted for the different education streams in Israel: state-run, religious state-run and Arab. Ministry officials also say that there are programs that have been adapted for the state-run ultra-Orthodox education system, but it is not known whether it is used and, in any case, only around 5 percent of ultra-Orthodox children are enrolled in state-run ultra-Orthodox schools. The vast majority of ultra-Orthodox students, in contrast, who are in any case much less exposed to the issue, learn nothing about their own sexuality in school or, for the most part, within the family. Galia Givoly, an attorney and lecturer at Tel Aviv University, has been researching various elements of ultra-Orthodox society. Her comments show that this is not a marginal phenomenon. “In 2021,” she tells Shomrim,” 27 percent of first-graders were studying in the ultra-Orthodox education system – and that number is growing every year.” In total, some 400,000 Israeli children are enrolled in ultra-Orthodox schools.

“only if the law is changed and every ultra-Orthodox is forced to teach 100 percent of the core curriculum and if that core curriculum includes mandatory sex education classes – only then will ultra-Orthodox schools start teaching the subject."

.jpeg)

Givoly points out that the ultra-Orthodox community enjoys educational autonomy, which means that independent educational streams can teach their students whatever they want. “Although laws have been passed which obligate the state to set a minimum in terms of compulsory subjects – Hebrew language, history, science and so on – and to supervise the schools to ensure that they meet this standard,” she says, “in practice this does not happen.” And when it comes to elements of the core curriculum which are more sensitive, the situation is even worse.

Dr. Michal Prins has written two books and hosts a popular podcast dealing with the issue of sexuality in the national-religious community. In recent years, she has also started to explore the same subject in ultra-Orthodox society. “There is a massive lack of knowledge. Women suffer from totally unsatisfactory education when it comes to their own bodies and they are also taught to obey a set of rules dictated to them by rabbis. Ultra-Orthodox men also suffer greatly from the same problem. There was a study which looked at the percentage of people being treated by welfare services for sexual abuse. In relative terms, there are far more victims of sexual abuse in ultra-Orthodox towns and cities – and dramatically more boys than girls.”

“ultra-Orthodox boys are educated to repress their sexuality and they pay a heavy price for this when they reach maturity. I encounter couples who experience terrible problems in their relationship because of all kinds of prohibitions, restrictions and the fears with which they grew up.”

Prins adds that the problem is not just vulnerability. “ultra-Orthodox boys are educated to repress their sexuality and they pay a heavy price for this when they reach maturity. I encounter couples who experience terrible problems in their relationship because of all kinds of prohibitions, restrictions and the fears with which they grew up.”

According to Prins, the problem stems both from a lack of formal and informal education. “The only formal education that a young ultra-Orthodox woman is given is before her wedding night – and even that is based on the understanding that there are certain things that a woman needs to hear before she marries. This is the first and last juncture at which girls are given any kind of information. It’s not very clear what they are told, how they are told it, what the bride understands and what the teacher says. There is, for example, one approach whereby the girls are told that the wedding night must be a success and that there must be full penetration on the first night, otherwise the ramifications could be serious and problematic [from a religious perspective – LS]. Do they talk about such things when instructing brides-to-be? Probably not.”

Prins stresses that the situation in terms of informal education is no better. “When a mother does not answer questions and dodges the whole issue, that is part of sex education. It sends a message. If her daughter asks a friend and that friend heard something from her cousin who heard from her big brother, she can get third-hand information. It’s also possible to find allusions in Jewish textbooks. All of this is considered informal education and the information children can glean this way could be problematic.”

Through her podcast, Prins tries to reach people directly. “I want to reach a mother who suddenly decides to open her eyes and check what’s going on with her children,” she explains.

‘I found a book on the train’

Shari, a 25-year-old economics student, is the daughter of newly religious parents who made every effort to integrate themselves into the ultra-Orthodox they joined. She was not sexually assaulted and no one harmed her, but the story of her adolescent years and the ramifications serve as an example of the problems caused by a lack of sex education.

“There was no sex education whatsoever, but there was a lot of informal and unspoken education. Things that you pick up on as a child,” she says. “I was raised to be demure and modest. And modesty is not just how you dress; it is something that is burnished into the way you think, in nuances. For example, knowing what to talk about and what not to talk about; it’s knowing not to sing in your own home if the windows are open; and it’s also knowing not to talk on the cellphone on the bus or to walk elegantly to the bus stop – because running isn’t modest. When I was 12 years old, all I wanted was to be a boy, because I felt that they could do whatever they wanted. They could climb trees when I couldn’t, for example, because it’s not modest.”

When she reached puberty, she adds, no one explained to her the changes her body was undergoing. “I refused to accept the fact that I was developing; I was worried that people would notice I was changing. I wore baggy shirts and there was a time when I was always wearing a coat – even in the sweltering summer heat. Any time the subject came up, I would burst out crying because of stress and anxiety. Since we were not a typical ultra-Orthodox family and we had a children’s encyclopedia, I knew what a period was.. One day, my mother said, ‘You probably already know about menstruation’ and even though I had read about it, I told her I only knew a little, because I didn’t want to embarrass her as a newly religious mother to an ultra-Orthodox girl. I was curious and I used to find books in the trash to read. Once, I found a book on the train called ‘What is happening to my body?’ I read every word but because of the context and the pressure around the subject, I don’t think it helped me. It became something that I did in secret, something that nobody else should find out about. Everyone needed to keep on believing that I was innocent.”

Shari has experienced a lot of turmoil in her life and her willingness to talk about the subject is because she has left the ultra-Orthodox community. The scars from an adolescence like the one she experiences are deep, she says. “I think that the reason I don’t stand up for myself and I am not assertive is closely linked to the messages I received then. By the same token, when I find myself in a romantic situation, I am scared, lost and I don’t know how to communicate. It took me a long time until I decided to start wearing pants or sleeveless blouses, until I dared to go to the beach (…) It is not specifically linked to sexuality, but, rather to the body, to physical presence. I was educated to be introverted, withdrawn and absent.”

‘Something’s strange here. I’m strange’

Efrat Peled Behar is a psychologist who runs group sessions, advises on healthy sexuality and works with several help centers. In recent years, she has been exploring the issue of sex education on the axis of child-adolescent development. “In adolescence, when sexuality is developing and the body is inundated with hormones, many changes occur. There is a lot of disproportion, both in terms of the biological organs and the parts of an individual’s personality, which are beginning to take shape,” she explains. “When one adds to that confusion and the physical changes send a message that the process is something not to be addressed or spoken about, the adolescent comes to learn that the changes are not positive, that they are wrong and forbidden. They think that if what is happening to them is not within the framework of things that people can talk about, then something’s strange here. I am strange.”

“Personal autonomy does not exist in the ultra-Orthodox sector, period. The insularity of the community and the fear of exposure to anything that could upset the status quo means that there is no education to autonomy in any way, shape or form – certainly not bodily autonomy."

.jpeg)

Peled Behar says that, in absence of education, boys in the ultra-Orthodox sector learn a lot of negative lessons about their own sexuality and that the ramifications are highly problematic. “After all, why do they go to the mikvah from such a young age? Because that’s when issues like nocturnal emissions, masturbation and involuntary ejaculation start. In a nonverbal way, they are told that what is happening to their bodies is wrong, that it is ‘dirty and vile’ and perhaps even dangerous to a certain degree, because they are serious implications for such behavior in Jewish law. All of this long list, of course, leads to negative emotions, to concealment and to shame.”

According to Peled Behar, sex education from a young age is vitally important. “First of all, we need to start with the principles of safety,” she says, “such as teaching children not to go with strangers or, for example, teaching them there is a difference between a good secret, which makes them feel good inside and makes them happy, a secret that they are allowed to tell their parents, and a bad secret, which makes them feel bad inside and which is accompanied by negative emotions such as fear, sadness, stress – the kind of secret that someone told them not to share with their parents. This way, children are given the tools to identify situations in which someone is trying to force them into a corner – so they have a better chance of not being abused. This is a tool that saves lives. It is also an example of a protection tool that is provided at a young age without using specific vocabulary or detailed explanations that would mean the end of childhood innocence.”

Even such a relatively innocent tool as one described by Peled Behar is hard to integrate into the ultra-Orthodox education system. “It is obviously important to combine lessons in protection and treating the body right into ultra-Orthodox schools, but I do not believe that it is possible given the current conduct there,” she explains. “Personal autonomy does not exist in the ultra-Orthodox sector, period. The insularity of the community and the fear of exposure to anything that could upset the status quo means that there is no education to autonomy in any way, shape or form – certainly not bodily autonomy. Moreover, the body is something that ultra-Orthodox individuals are told to subjugate to the spirit. When the instruction to follow religious edicts without question is so strong, anything that could lead to a discussion is inaccessible, so how can anyone even start to talk about the right to autonomy over anything personal? It fundamentally violates the central tenet of how this community protects itself.”

‘The boarding school called it “messing around” and covered it up’

Shalom, 23, was raised in an ultra-Orthodox family in Jerusalem and was sent away to boarding school, where he was sexually abused. His case touches on almost every problematic element of the ultra-Orthodox community’s behavior when it comes to sexual assaults and abuse: insularity, a lack of education and awareness – and silencing victims. “Home life was never easy,” Shalom tells Shomrim. “My father emotionally and physically abused me and my mother. But I was not sent to the boarding school for that reason. Rather, I was a ‘different’ child, with attention disorders and Tourette Syndrome, which meant that I couldn’t study in a yeshiva and I was defined as a disappointment.

“I was sent to an ultra-Orthodox therapeutic boarding school, which was divided into smaller groups of daycare centers. When I was 14, a boy who was three or four years older than me and who was in the same room as me, abused me. He started by teaching me about things I knew nothing about and areas I was completely ignorant of – and he gradually started to abuse me and did things to me against my will. He attacked me and was even violent toward me. That was my first encounter with the subject of sex. I knew that it was pleasurable sometimes, but most of the time it really was not.

“The same youth attacked several other children and when it all came out, he mentioned my name as well. It was sexual assault that lasted a whole year, but the boarding school called it ‘messing about’ and covered it all up. The most difficult part for me was that my parents were mad at me and accused me of violating the rules, of being a troublemaker, of not being okay. Just like the school, they wanted to sweep it all under the carpet and that’s where it ended.”

The trauma that Shalom experienced changes his life. “I can feel the scars from the abuse everywhere; in my difficulties dealing with things and feeling that I am worth something; in my difficulties not feeling like a beaten child. For years, I would walk the streets and feel attacked and I would shrink inside myself. Just recently, I noticed that this is my body’s automatic reaction, because my soul is scared.”

According to Shalom, “one of the reasons that I want to help people who are experiencing similar things is that I believe that my experience will help me understand them. I know what it is to feel totally alone, what it’s like to grab hold of something and hold onto it tight, as if you’re being blown about by a hurricane. It takes time to emerge from a long period of difficulties, but it’s a process and I’ve got the time.”

.jpeg)

Where, if anywhere, will change come from?

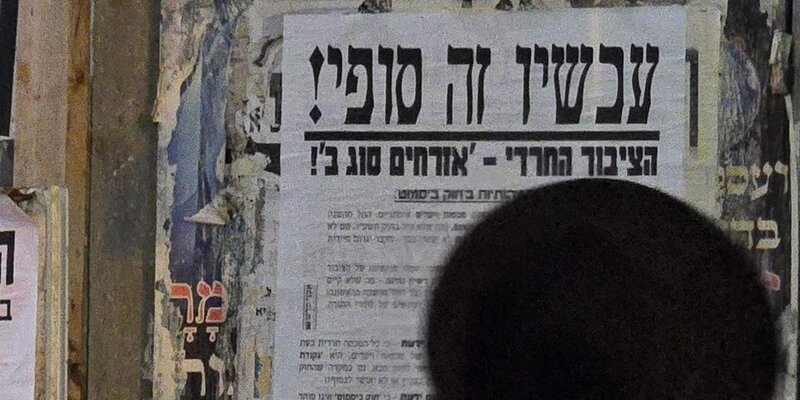

Shalom’s harrowing case highlights the urgent need for change – a change that does not currently appear to be imminent. Where could this change come from? The experts interviewed for this article were divided in their answers. Givoly, for example, believes that “only if the law is changed and every ultra-Orthodox is forced to teach 100 percent of the core curriculum and if that core curriculum includes mandatory sex education classes – only then will ultra-Orthodox schools start teaching the subject. Otherwise, there is no legal way of enforcing this change on them. Even educational institutions that are required to teach part of the core curriculum can, of course, choose not to teach these parts.”

Others believe that change can come from within ultra-Orthodox society, through community organizations like Hineini for the Community, an NGO that advocates for sex education in the up community and offers assistance to victims of sexual abuse. And there are those who are convinced that change will not come from within and there could be strong backlash to any attempts to address the issue. “Many more ultra-Orthodox people would demonstrate against sex education in their schools than are currently protesting against the draft of yeshiva students,” says one of them.