Foster Parents to Foreign Children Don’t Understand Why the Children are Taken Away Without Warning

The testimonies keep repeating themselves: A foreign child lives for years with an Israeli foster family, and then, after the case is transferred to Tel Aviv Municipality’s Mesila unit, something changes. Suddenly, the authorities want to get the child back with the biological mother as quickly as possible, even if nothing has changed regarding her ability to raise him. Along the way, the foster families claim, there are lies, dismissive attitudes, and a lack of concern for the children’s welfare. A joint investigation by Shomrim and Haaretz newspaper

.jpg)

.jpg)

The testimonies keep repeating themselves: A foreign child lives for years with an Israeli foster family, and then, after the case is transferred to Tel Aviv Municipality’s Mesila unit, something changes. Suddenly, the authorities want to get the child back with the biological mother as quickly as possible, even if nothing has changed regarding her ability to raise him. Along the way, the foster families claim, there are lies, dismissive attitudes, and a lack of concern for the children’s welfare. A joint investigation by Shomrim and Haaretz newspaper

.jpg)

The testimonies keep repeating themselves: A foreign child lives for years with an Israeli foster family, and then, after the case is transferred to Tel Aviv Municipality’s Mesila unit, something changes. Suddenly, the authorities want to get the child back with the biological mother as quickly as possible, even if nothing has changed regarding her ability to raise him. Along the way, the foster families claim, there are lies, dismissive attitudes, and a lack of concern for the children’s welfare. A joint investigation by Shomrim and Haaretz newspaper

Einat and Arik. Photo: Bea Bar Kallos. Illustration: Masha Zur Glozman (Haaretz)

Daniel Dolev

March 5, 2023

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

For more than two and half years, Shlomit was a single mother to Keren (both of whom appear under false names in this article). She knew in advance that her parenthood was for a limited time, she didn’t know how long it would last. Shlomit was chosen as Keren’s foster mother when she was eight months old. Welfare authorities ruled at the time that Keren’s biological mother, an asylum seeker from Eritrea, was not in a position to look after her daughter. Shlomit’s fostering of Keren was conditional, however. Unlike fostering Israeli children, who can be adopted by their foster parents a few years later, the situation is a lot more complex regarding the children of foreign nationals.

Everything went smoothly during the first two years, but Shlomit was informed suddenly that it had been decided to remove the child from her care – even though there had been no problems raising her and, in theory, there had been no change to her status. The only thing that had changed, it seems, was that Keren’s case had been transferred from Tel Aviv Municipality’s Welfare Department to Mesila – the municipal unit which provides assistance and social services to asylum seekers and undocumented people.

She is not the only one who feels this way. Haaretz and Shomrim have received testimony from four families who fostered children of foreign nationals, whose stories bear many similarities. Moreover, a fifth family came to our attention, which, in closed forums, described experiences very similar to the people interviewed for this article. They all make the same central point: The change for the worse happened the moment that the foster file was transferred from the various municipal welfare departments to Mesila, a process that was completed in recent years. Since then, they say, they were treated disparagingly by officials, threatened, and lied to, according to their court testimonies. Moreover, they say, Mesila ignored professional opinions and acted in a way that seemed to have just one goal: getting the children back to their biological mothers no matter what, even at the expense of the children themselves.

“The last six months with Keren were emotionally insufferable,” says Shlomit. “I felt the whole time that Mesila was terrorizing me.” She says that from the first meeting she attended with committee members after the change in auspices, it was clear that there had been a decision to return the child to her biological mother. “Since then,” she adds, “everything just got worse.”

Shlomit is referring to the Welfare Department’s Planning and Treatment Committee, which reevaluates the need for continued fostering at least once a year. The final word on whether to accept or reject the recommendations of the Welfare Department belongs to the Family Court. In Shlomit’s case, the court rubberstamped the deterioration.

Shlomit believes that the process of returning Keren to her biological mother was too fast. During the fostering period, she says, Keren had not spent any prolonged period of time at her birth mother’s home, and any time she did spend there was on the weekend when the mother did not have to take her to kindergarten. According to Shlomit, she wanted to bring the issue up with Mesila officials, but they “explicitly told me that the mother cannot look after her daughter during the week because she works.” Shlomit realized she was being lied to. “I knew the mother had been out of work for several months.”

In general, Shlomit feels like she has no one to talk to. “The Mesila social workers didn’t even bother trying to engage in dialogue with me,” she explains. “I told them all the time that I would be happy to sit and think together about what’s best for the child.” However, she says that it was like talking to the wall.

Before Keren was returned to her mother’s custody full-time, Shlomit noticed that when she returned from visiting her, she was “very hungry or exhausted, but no one said anything about it.” Indeed, she says, no one listened when she tried to complain about what was happening in the biological mother’s home. One time, she even reported something “disturbing” that she said happened there. “They told me it’s being dealt with. I live in Israel, so I know just how little that means. I had a feeling it was being swept under the rug.”

“The last six months with Keren were emotionally insufferable,” says Shlomit. “I felt the whole time that Mesila was terrorizing me.” She says that from the first meeting she attended with committee members after the change in auspices, it was clear that there had been a decision to return the child to her biological mother. “Since then,” she adds, “everything just got worse"

From the ‘Warehouse’ to the Home

According to figures from the Welfare Ministry, there were 5,470 children in foster homes in 2021, most of whom were with relatives. Of them, 60 were the children of foreign nationals. The numerical gulf is not the only difference between the two groups. While Israeli children can be adopted by their foster families after a few years, to adopt a foreign child, the foster parents have to obtain approval from the mother’s country of origin. This is frequently also a complex diplomatic issue, to put it mildly. In the case of Eritrea, there is no point even trying to obtain approval, welfare officials told Haaretz. After a well-publicized case two years ago, these officials say, the government in Asmara informed Israel that it would not approve the full adoption of any children born to its nationals in Israel. Similar messages have recently been relayed from the Philippines and, since the influx of refugees from Ukraine, from Kyiv as well. This leaves the foster parents and the children themselves in a state of limbo. To an outside observer, they may appear to be just like any other adopted child, but, in practice, their status in Israel is determined by that of their biological mothers. And so, even though the number of children involved is small, the Interior Ministry refuses to give them any official status in Israel – even temporarily.

The story of Nadav Bossem and his partner, Hezi Cohen, who are the only couple who agreed to be identified by their full names for this article, begins in 2013. At the time, Cohen was volunteering at one of the kindergartens for foreign children in south Tel Aviv – kindergartens that became known as “child warehouses.” One day, he noticed that no one had come to pick up one of the children. He investigated the matter and discovered that the biological mother was finding it hard to look after her toddler, who was two years old at the time. Cohen says that they reached an agreement, with the mother’s knowledge, whereby the child, Adam, would spend weekends with the couple, who would later become his foster parents. That was the uninterrupted routine for six years until, in 2019, the biological mother said she wanted to be back in her son’s life. Cohen and Bossem had no problem with this; they even said they were delighted for the boy. But the process mapped out by the social worker from Mesila was very quick. “It went from meeting once every two weeks to a weekly meeting, from two to four hours,” says Bossem. “They were dashing without seeing that people were involved. Not just Hezi and me, but the child and his mother.”

They say that Adam would return frustrated from these meetings with his mother. “When we told [Mesila] about it, they said we’re making it up, and then they said that the child was making things up,” Bossem says. He adds that a psychologist who was involved in the story on behalf of the official supervisor of foster care was also opposed to the frequency of these meetings “because she said that it does not help the child – and the moment that she made her opinion known, she was removed from the process.”

The escalation in tensions between the couple and Mesila came in September 2019, when the committee convened to decide on Adam’s fate for the following year. According to Bossem, he and Cohen were only informed that the committee was meeting one day beforehand, and since they could not attend, it was held without them. It was decided that Adam would be returned once and for all to his biological mother within three months.

Although foster parents do not have any legal standing at these hearings, it is usual to hear what they have to say – as well as the minor whose fate is being discussed, represented by their guardian and a representative of the official supervisor of foster care (a private body which trains and supervises foster parents) – before the welfare department formulates its recommendations, which are then submitted to the Family Court. In this case, Cohen and Bossem say, they were forced into silence.

But that was just the preview to the big explosion, which happened shortly afterward. At the end of one of his meetings with his mother, Bossem says, Adam told them that he had been informed that “he was going to sleep at his mother’s house from now on.” Out of the blue, on the very same day. “He didn’t have anything with him,” Bossem says. “Not clothes, not his school bag for the next day. Nothing. So Hezi, who was already stressed out, opened his mouth.” From that point on, everything deteriorated very quickly, and at the request of Mesila, a restraining order was taken out against the couple.

The day after the restraining order was issued, a Mesila social worker, accompanied by a police officer, showed up at Adam’s school. “They took him to one side and told him, ‘You’re going to live with your mother now, and you won’t see your daddies again until you’re 18,” Bossem claims. One Welfare Ministry official aware of the case in real-time says that he was shocked. “I have never seen anything like that. We tried to get the restraining order canceled so that the foster parents could see Adam, but Mesila objected.”

Once Adam was returned to his mother’s custody, the foster couple was allowed to see him for short periods and under supervision, but the friction continued. “They would watch us,” says Bossem. “If we asked him if he was okay, they said we were stirring up trouble between him and his mother. We brought him his bus pass, which didn’t even have any credit on it, and they accused us of trying to bribe him.”

Last August, Adam, and his mother, like many other asylum seekers, left Israel for Canada. “A day before they left, they called us up at 3 P.M. and asked if we wanted to see him at 5 P.M. – in just two hours – for half an hour because they were leaving the next day,” Bossem says. “That showed us how transparent we were to them, unimportant.”

Once Adam was returned to his mother’s custody, the foster couple was allowed to see him for short periods and under supervision, but the friction continued. “They would watch us,” says Bossem. “If we asked him if he was okay, they said we were stirring up trouble between him and his mother. We brought him his bus pass, which didn’t even have any credit on it, and they accused us of trying to bribe him"

A Brother in Every Way

All the foster parents who spoke with Haaretz and Shomrim asked to stress that their only complaints were directed at Mesila, and not the biological mothers. Many of them have remained in contact with the mothers over the years – and not only because the mothers maintain the right to veto significant decisions about the child’s future. Sometimes, this goes beyond constant dialogue between the foster parents and the biological mothers, and a real bond of friendship can develop. Shlomit, for example, helped Keren’s mother find work. For Einat and Arik, it went much further than that. Over time, they say they developed a powerful bond with Yair’s biological mother. She would come to their home, sleep over on weekends, and even consult with them about issues unrelated to the child.

Einat and Arik became Yair’s foster parents before his third birthday, and he stayed with them for nine years. He became an integral part of the family, a brother in every way to their biological children. But then there was a committee meeting in August 2021. At that stage, the case was not entirely in the hands of Mesila, but a social worker representing the organization had already attended one hearing. “We emerged with a feeling that she saw us as some kind of child snatchers,” says Arik. Einat remembers that before the hearing, the biological mother told her that one member of the Mesila team had given her 1,000 shekels in vouchers and told her, “If you want us to keep helping you, you have to say that you want your child back.” Haaretz and Shomrim asked Mesila for its response to this case, but the organization declined.

Independent of this claim or not, the biological mother asked to be given custody of her son but agreed to extend the foster arrangement for another six months. The committee decided to extend it by one year. Einat and Arik were relieved, but that was short-lived. Some two months later, they got a phone call from the Orr Shalom non-profit foster organization, telling them that the case had been handed over to Mesila. Moreover, they learned that Mesila had decided – on its own accord and without holding any additional hearings – to overturn the committee’s decision and insist that Yair would be returned to his biological mother by June.

That kicked off a protracted legal struggle, which went from the Magistrate’s Court to the District Court and from there to the Supreme Court, ultimately deciding that Yair should be returned to his biological mother more gradually. “The minor is of Eritrean extraction and a member of the Christian faith,” Justice Daphne Barak-Erez wrote in her ruling. “It is only natural that we consider the importance of the sense of identity and belonging which the foster family cannot provide him.”

When retired judge Saviona Rotlevy read those words, she found it hard to conceal her anger. “When judges take the position that children with darker skin or who are Christians must be in exactly that kind of environment, I simply don’t understand it,” says the judge who headed the committee whose report forms the basis for the adoption laws in Israel. “How can they say this is the main element in the child’s welfare?”

Prof. Asher Ben-Arieh, dean of the School of Social Work and Social Welfare at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, shares Rotlevy’s fury. “I cannot escape the feeling that, within Mesila’s clear preference in favor of the biological parents, there is a desire to see foreigners living with foreigners,” says Ben-Arieh, who also heads the Haruv Institute, which specializes in training and engaging in research to help children suffering from abuse and neglect.

And now another hypothesis, raised by experts in the field and not denied by any official from the welfare authorities, enters the equation. Given that Israel does not give residency status to parents from Eritrea and Sudan and tries to think of ways to expel them, there is a concern that having their children in foster care will make it harder to deport the parents – or force the families to be separated. “How come there has suddenly been a sequence of cases like this, where the foster arrangement was annulled in cases where the parents were here illegally or were long-term candidates for deportation,” Ben-Arieh asks. “And why have I not seen a similar trend among Israeli children in foster care?”

Rotlevy, who has met all the families interviewed for this article, goes even further in her conclusion. “It’s simply racism, designed in the end to get as many of them out of Israel as possible, by hook or by crook,” she says. “The way that it is being done, by tearing the children away from the parents who have been raising them for years, also infuriates me in terms of ignoring the will of the child. They simply don’t care about that.”

After the case reached the Supreme Court, the process of returning Yair to his biological mother picked up pace – against the child’s wishes. “They were terrible months,” say Einat and Arik about that period, when any objection on their part, no matter how minor, was greeted with a tacit or explicit threat that a court order would end the gradual process and Yair would be taken away overnight.

In the end, Yair returned to his biological mother’s custody gradually. On the day after the process was completed, something happened that needed medical attention. “He refused to go because no one would tell him what was happening,” Einat says tearfully. “The poor kid was heartbroken, and some social worker told him that if he didn’t go with her, she would call the cops and they would take him away.”

It has been six months since then. According to the foster parents, Mesila officials continue to make it hard for them to meet with Yair. The bottom line, says Einat, “is that there are so many victims in this story. Obviously, the biggest victim of all is Yair, but as far as I am concerned, his mother is also a victim here.” Attorney Barak Cohen, who is representing another non-Israeli biological mother and her child, who is in foster care, agrees with that. According to Barak, who stresses that he is expressing his personal opinion alone, “there is a profound moral prohibition on fulfilling the experience of parenthood by means of taking the children of the weakest members of our society – refugees – among the most privileged, affluent and connected people in Israel.”

“We emerged with a feeling that she saw us as some kind of child snatchers,” says Arik. Einat remembers that before the hearing, the biological mother told her that one member of the Mesila team had given her 1,000 shekels in vouchers and told her, “If you want us to keep helping you, you have to say that you want your child back"

On Borrowed Time

The case of Yoel and Ella is slightly different. Their foster son, Doron, is almost ten years old and still lives with them. But they know they are living on borrowed time since their case was transferred to Mesila a few months ago. “From that moment on, everything has been done very quickly,” says Yoel. “Members of the team haven’t visited the boy even once. They don’t know him at all. They also didn’t invite representatives from his school to come and give their opinion.” On June 12, the committee convened under new management. “They asked us to describe Doron’s situation, and then the psychologist who treated him gave her opinion. She said that she believed any decision to return him to his biological mother would have negative consequences. Even suicidal thoughts.” However, he says, Mesila tried to discredit everything she said. “Even before she started to give her opinion, they asked if she was qualified to treat children.”

Doron has been living with Yoel and Ella for six years, but the committee had already decided that there would not be a seventh year – certainly not a full one. They were given six months. After the decision was made, Yoel managed to get a meeting, along with other foster parents, with the director general of the Welfare Ministry at the time, Sigal Moran. At that meeting, Yoel told her about the conduct of the committee and was told that the decision reached at that hearing had been overturned – without any further explanation. The reversal left them with some room for optimism, but that quickly vanished. Orr Shalom called Yoel on August 31, informing him of the new timetable: Doron would be taken to his biological mother’s house the next day – somewhere he had never been before. A week later, a Mesila team would visit the house, and another committee hearing would be held. That was delayed, but not for very long. It was recently decided that, within six months, Doron would return to his biological mother.

Tel Aviv Municipality submitted the following response

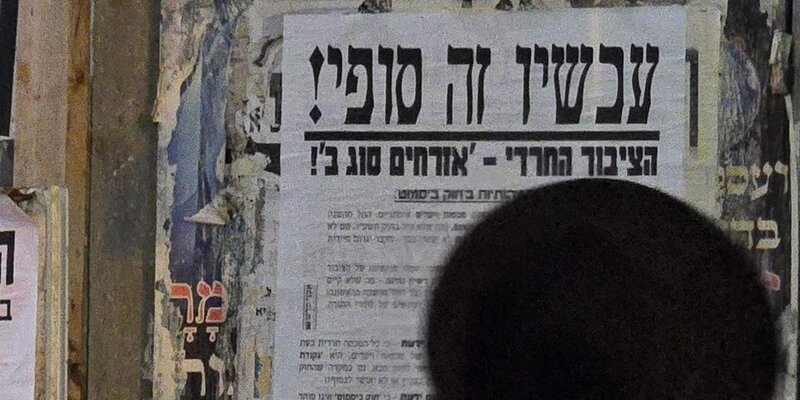

“We have examined the claims made by the foster families very seriously. We are aware of the pain suffered by foster parents, who occasionally have to say goodbye to children they have raised with love and dedication, and we thank them for that. At the same time, some of the foster parents to children from the statusless community do not obey the decisions of the courts, and it seems that they have decided to blacken the reputation of Mesila – simply because, in some of the cases, the courts ordered the children returned to their biological parents. In each of the cases, Mesila was only interested in the child's welfare and, in any case, acts according to the instruction of the courts and the law.”

The municipality added, “it is hard to ignore the fact that these are wealthy foster families dealing with biological mothers who are statusless, refugees, impoverished, and unlike the foster families, cannot fight against the large and powerful system to get their children back. By all accounts, whenever the foster family has asked for its say, it has been allowed to speak before the court. In some of the cases that appear in the article, an appeal was filed, and a decision was handed down. In addition, in some cases, the Welfare Ministry was a full partner in the decision. We would also point out that even when the minor was returned to the biological parents, unless there were extreme circumstances, the foster families continued to be in contact with the child, with the minor's best interests at heart.

“To protect their privacy, we will not mention names, but we will say that one of the foster families mentioned in the article harassed the biological mother of the child they fostered in an attempt to damage the relationship between mother and child.

“With every understanding of the pain of the foster families, after a long period of attacks against female public service workers, we believe that the time has come for those families to accept the fact that their fostering has ended and to be glad that the children in question are back with their biological parents. A minor’s right to be raised by their parents cannot be underestimated as long as they are capable of raising them. This is something that only the court can determine. It is important to stress that we are talking about a handful of foster families, where dozens of statusless children are placed in foster homes or boarding schools by the courts.”