Deri’s Food Vouchers Favored the Ultra-Orthodox Over Other Vulnerable Communities

In the Ultra-Orthodox town of Modi’in Illit, residents got an average of 530 shekels. In the Bedouin regional conuil Neveh Midbar in the Negev – just 14 shekels apiece. Former Interior Minister Aryeh Deri’s food voucher initiative distributed 700 million shekels ($200 million) to needy citizens. An analysis of the data – made available only after a freedom-of-information request – shows that the Ultra-Orthodox got significantly more of the money than other vulnerable communities. Deri declined to comment on this article. A Shomrim investigation, published in conjunction with Calcalist [Hebrew]

.jpg)

.jpg)

In the Ultra-Orthodox town of Modi’in Illit, residents got an average of 530 shekels. In the Bedouin regional conuil Neveh Midbar in the Negev – just 14 shekels apiece. Former Interior Minister Aryeh Deri’s food voucher initiative distributed 700 million shekels ($200 million) to needy citizens. An analysis of the data – made available only after a freedom-of-information request – shows that the Ultra-Orthodox got significantly more of the money than other vulnerable communities. Deri declined to comment on this article. A Shomrim investigation, published in conjunction with Calcalist [Hebrew]

.jpg)

In the Ultra-Orthodox town of Modi’in Illit, residents got an average of 530 shekels. In the Bedouin regional conuil Neveh Midbar in the Negev – just 14 shekels apiece. Former Interior Minister Aryeh Deri’s food voucher initiative distributed 700 million shekels ($200 million) to needy citizens. An analysis of the data – made available only after a freedom-of-information request – shows that the Ultra-Orthodox got significantly more of the money than other vulnerable communities. Deri declined to comment on this article. A Shomrim investigation, published in conjunction with Calcalist [Hebrew]

Former Interior Minister Aryeh Deri. Photo: Reuters

Daniel Dolev

April 3, 2023

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

Ultra-Orthodox cities were at the top of the list, and Bedouin communities were at the bottom: that was how government assistance for buying food was distributed by the Interior Ministry, under then-minister Aryeh Deri, during the coronavirus pandemic. The current coalition agreement between Likud and Shas guaranteed another 1 billion shekels ($273 million) to be distributed in a similar manner.

In late 2020, when the coronavirus pandemic was at its most intense and just after the 23rd Knesset was dissolved, the Interior Ministry unveiled an initiative aimed at helping vulnerable families experiencing food insecurity. The central idea of the proposal was to distribute 700 million shekels to families in need using a reloadable credit card for purchasing food. The criterion for receiving the aid was that the recipient already be eligible on an ongoing basis for a 70 percent discount in municipal taxes; anyone meeting this requirement would automatically qualify for a card. Anyone not already receiving the discount would have to submit an individual request and prove they meet the financial threshold. Money was transferred to the recipients in three stages; in total, every family received up to 7,200 shekels.

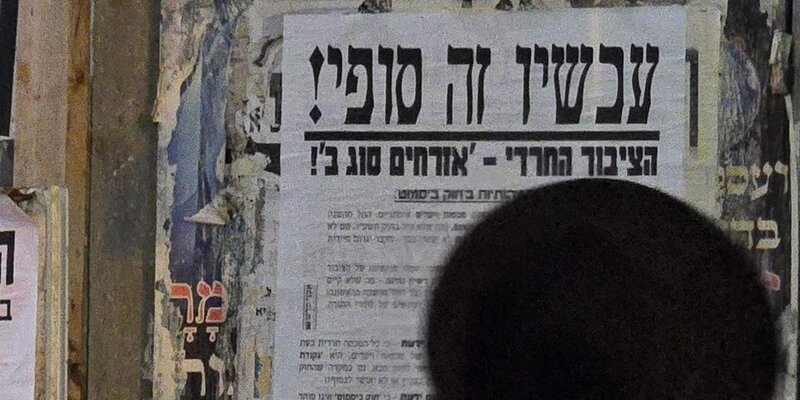

The initiative’s reception was contested, in part because it was entrusted in the hands of the Interior Ministry and not, for example, with the Welfare Ministry. Moreover, the National Council for Food Security – the government body established for precisely this purpose – was left out of the plan entirely. The fact that the initiative was launched so close to a general election, coupled with the criterion for receiving the assistance, gave rise to suspicions that the ministry was engaged in “election economics.” Suspicions were only exacerbated when, during the campaign season, posters with Deri’s name and face appeared in ultra-Orthodox cities – alongside a reminder about the food cards.

As Shomrim reported at the time [Hebrew], the argument was that the criterion for receiving the food assistance – which was, as mentioned, linked to eligibility for a municipal tax discount – was concocted specifically with the ultra-Orthodox community in mind. The Movement for Quality Government in Israel petitioned the Supreme Court, submitting to the justices an analysis of Interior Ministry data, which showed that in communities with an ultra-Orthodox majority, 45 percent of households were eligible for a discount in municipal taxes. In non-Jewish communities, the data showed that just 25 percent of households were eligible for the discount.

“Using this criterion raises the suspicion that preferential treatment would be given to communities closely associated with the interior minister,” the petition argued. “In light of the obvious result that the ultra-Orthodox community, compared to its relative size in the general population, would benefit disproportionately from this subsidy, and given the fact that this community is closely associated with the interior ministry, there is a very real concern that the criteria have been ‘fixed’ for the benefit of a certain group.”

Justice Alex Stein rejected the petition, stating that the interior minister’s policy was reasonable since “the criteria for receiving the subsidy in question were adapted to the economic situation of people in need.”

The fact that the initiative was launched so close to a general election, coupled with the criterion for receiving the assistance, gave rise to suspicions that the ministry was engaged in “election economics.”

The Real Data

Several months ago, Shomrim submitted a freedom-of-information request to the Interior Ministry, asking for data regarding the distribution of the food subsidies. An analysis of this data shows that the ultra-Orthodox population benefited from the handout at a much higher rate than other vulnerable communities. The data we received included the number of families who received a rechargeable credit card for purchasing food in each community, as well as the total amount that was distributed to each community. Shomrim cross-referenced this data with the size of the population, which allowed us to calculate the amount of assistance distributed ‘per resident’ for every Israeli city. To avoid making a comparison between wealthier and more vulnerable communities, the analysis focused exclusively on communities in the first and second socioeconomic clusters – which are the lowest clusters as defined by Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics.

The result is indisputable. In first place on the list is the ultra-Orthodox town of Modi'in Illit, where 8,780 families received the rechargeable credit card at a total cost of 40 million shekels. On average, residents of Modi'in Illit received 530 shekels each in the framework of the initiative. Second on the list was another ultra-Orthodox town – Beitar Illit – where residents received an average of 397 shekels.

Those two ultra-Orthodox towns, it should be stressed, are among the most vulnerable and impoverished communities in Israel and are both in the lowest socioeconomic cluster. The remaining nine communities in that cluster are all Bedouin towns and local councils in southern Israel. But they lag far behind the ultra-Orthodox towns. For example, in Rahat, which is approximately the same size as Modi'in Illit, just 2,456 families received the food card, and on average, the residents of Israel’s only Bedouin city received 129 shekels each.

In Tel Sheva, a Bedouin township in the northern Negev, residents received an average of 67 shekels each, while in nearby Hura, the average was 55 shekels. Residents of the Al-Kasom Regional Council were given an average of 18 shekels each. At the same time, those in the Neveh Midbar Regional Council – which, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics, is Israel’s most impoverished community – got just 14 shekels on average.

The data also shows that there were 1,378 families from the Bedouin diaspora who received subsidies totaling 3.6 million shekels but who were not part of any community. Even if all of this amount were to be divided up between the two Bedouin regional councils in southern Israel, it might improve somewhat their position in the ranking, but it would do nothing to change the overall picture – which has the ultra-Orthodox communities at the top and the Bedouin at the bottom.

In fact, the assistance given to Bedouin communities was so pitiful that even two random communities from the fifth and sixth economic clusters that were analyzed – Dimona and Shlomi – benefited more from the assistance.

“A lot of people here live in unrecognized villages [where any kind of construction is illegal – D.D.], so there is hardly any municipal tax levied here at all, and that criterion is less relevant,” one welfare official in a Bedouin regional council in southern Israel tells Shomrim. For this reason, residents who wanted to receive food aid had to submit individual applications. The problem was that the hotline that the Interior Ministry opened to handle these questions was almost impossible to reach, and waiting times were very long – a fact that was also mentioned in the State Comptroller’s Report into the initiative – which made it hard for people to get updates about the status of their requests or to supply additional information when asked to do so.

At the same time, the welfare official says, many residents of these communities use prepaid phone cards, meaning they change their phone numbers frequently. This made it difficult for the Interior Ministry to subsequently contact them and update them about the status of their requestions. “There are also people here who cannot read, or maybe did not understand the messages they were sent,” the official believes. “It’s also a challenge for us to reach these people, and sometimes we have to go out into the field to find them,” he adds.

These reasons would seem to explain why, in the two Bedouin regional councils where most residents live in unrecognized villages – Neveh Midbar and Al-Kasom – between 37 and 40 percent of the requests for assistance were rejected, compared to a national average of just 7 percent. And as mentioned, residents of these two councils received the lowest average payout of residents in any community in the two lowest socioeconomic clusters.

.png)

As Shomrim reported at the time, the argument was that the criterion for receiving the food assistance – which was, as mentioned, linked to eligibility for a municipal tax discount – was concocted specifically with the ultra-Orthodox community in mind

Ultra-Orthodox on Top Again

At the top of the list of beneficiaries are the ultra-Orthodox towns of Modi’in Illit and Beitar Illit. Immediately after them, the communities which enjoyed the most generous per capita payout were the ultra-Orthodox settlement of Immanuel (382 shekels per resident) and the ultra-Orthodox community of Rekhasim in northern Israel (375 shekels) – both of which are in the CBS’s second socio-economic cluster. In fifth place is the Arab community of Ilut, also in the second socio-economic cluster, with an average of 363 shekels per resident, followed by Bnei Brak, with 319 shekels.

Most of the communities included in the first and second socioeconomic clusters have a very specific nature: they are either ultra-Orthodox, Arab, or Bedouin. This allows us to know which communities benefited in practice from the food cards. On the other hand, the more heterogenous a community is an analysis of the per-resident average leads to a less accurate picture. Among the ten communities that received the highest amounts from the food card initiative, you can also find Jerusalem (108 million shekels) and Ashdod (25 million shekels). In both these cities, there is an ultra-Orthodox community numbering between 20 to 30 percent of the population, but there are also other vulnerable populations, such as new immigrants and Arabs, so the figures do not allow us to ascertain whether the ultra-Orthodox residents were also the main beneficiaries of financial assistance in these cities.

Moreover, an examination of the assistance that each family received on average, based on the number of people per family, ultra-Orthodox communities still occupy the top five places: Modi’in Illit first with 4,613 shekels per family, followed by Elad, Beitar Illit, Beit Shemesh and Kiryat Ya’arim. Having said that, Rahat, Al-Kasom, and Neveh Midbar all appear in the top 10.

The distribution of financial aid is especially relevant when looking toward the future. The coalition agreement signed with Shas determines that the Interior Ministry will receive an additional 1 billion shekels a year to distribute in a similar manner. A recent report in the financial daily Calcalist [Hebrew] revealed that an agreement was reached during budget negotiations to cut the initiative to 250 million shekels this year and raise it to 500 million in 2024. In comparison, the food security initiative spearheaded by the Welfare Ministry and the National Council for Food Security receives an annual budget of just 100 million shekels.

.jpg)

Dr. Roni Strier, the National Council for Food Security chair, is appalled by the figures. “It’s terrifying,” he says. “This is a clear case of discrimination against social groups underutilizing their rights – and it is an absolute travesty."

It’s Terrifying

Dr. Roni Strier, the National Council for Food Security chair, is appalled by the figures. “It’s terrifying,” he says. “This is a clear case of discrimination against social groups underutilizing their rights – and it is an absolute travesty. The State Comptroller of the Supreme Court should have intervened because this is taking advantage of a very painful issue – food insecurity, children going hungry – for extraneous purposes.”

According to Strier, the Finance Ministry representatives in the Council told him that if the next budget will allocate the discussed funding to the Interior Ministry, it will be at the expense of expanding the Council’s own food security program. However, while the Council’s program offers families various additional services to help them with their financial conduct and food security, the food cards program offers only financial assistance.

“All of the research shows that, if you want to help these families, it’s not enough to hand them a sum of money once or twice a year,” says Strier. “You need to accompany them every month with a framework of services and support, which includes occupational empowerment, sound financial conduct, workshops on healthy eating, and work with the health services. This is included in our food security project, while the Interior Ministry’s food card program has nothing of this sort. It’s a card for handing out money. I am not opposed to money being given to low-income families with many children, but there is no research to indicate that this does anything to help with food security.”

Strier adds that, according to a recent study, just 16 percent of the families who receive support from the national food security project are entitled to the discount in municipal taxes that would automatically entitle them to the food card.

Latet, a non-profit aid organization, which provides regular assistance to tens of thousands of families experiencing food insecurity, says that its rate is slightly higher – around 28 percent of the people it helps are entitled to the Interior Ministry’s food card. They reached a similar conclusion: most of the assistance given out through the food cards did not reach people needing it most – families suffering from extreme food insecurity.

“If you really want to help people experiencing severe food insecurity, the criteria must closely match the profile of people in that category,” says Eran Weintrob, executive director of Latet. “In this context, there is a survey written by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which was adopted by Israel’s National Insurance Institute and used by the national food security program. We use it too. It’s the most reliable and accepted way to understand food insecurity, and there are also tests for people receiving supplemental income, family support, and more. These are criteria that are highly suited to people who are experiencing food insecurity and poverty.”

Weintrob adds that the way the money is distributed is also significant. He believes that the food card program gave too much weight to the number of people in each family, while the national food security program – which allocates 500 shekels for each family, irrespective of the number of members – errs toward the other extreme. The last thing that we would recommend – and this is a very fundamental point – is that the money must be handed out every month, throughout the year, and not in one or two payments. We’re just before the Passover holiday, and there’s always a lot of preparations to be made at this time of year, but these people will need help buying food after the holidays, too.”

Looking toward the future, Weintrob still holds out hope that the government will still hand over the hundreds of millions of shekels it has promised to deal with food insecurity, including a 100-million-shekel increase in the budget it allocates to NGOs that provide food. “We have a historic opportunity to make a significant change by expanding government responsibility to include food security,” he says. “For decades, the state, through social workers in the local authorities, sends people in poverty to the NGOs – who now assist more than 100,000 families on an ongoing basis. So, we expect the government to take full responsibility for this issue, but as long as the NGOs continue to operate, it is an issue we must keep addressing.”

Interior Ministry Response:

'The Food Voucher Program is Unprecedented in Its Scope'

The Interior Ministry submitted the following response to Shomrim: “The food voucher program, which is unprecedented in its scope, and which was advanced by the Interior Ministry under the leadership of former minister Rabbi Aryeh Deri, was launched in early March 2021 at the height of the coronavirus pandemic and has distributed vouchers to more than 350,000 Israeli households. This funding was given as a one-time payment for the purchase of a limited amount of food, which is capped at 7,2000 shekels per family in total for the entire period. The money was distributed extremely successfully, with distribution rates over 95 percent.

“Those people eligible for a discount in municipal taxes are the most vulnerable, including people entitled to supplemental income, welfare stipends and Holocaust survivors. The question of incompatibility in the distribution [between impoverished communities and the actual distribution of the funds – D.D.] could stem from several professional reasons. Among them:

“1. Discrepancies between the population data served by the local authority and the population data recorded by the Interior Ministry’s Population Registry – for example, residents of the [Bedouin] diaspora. There is a significant discrepancy in Bedouin councils that distorts the Population Registry\s figures and does not accurately reflect the number of residents served by the local authority. We set up a special hotline for residents of the diaspora, and the food vouchers that were handed out to this population were not reflected by the local authorities themselves.

“2. The ministry tried to make it as easy as possible for people to exercise their rights – but, because many of the people in question were concerned that receiving the food voucher would be linked to municipal tax payment or that they would subsequently be asked to pay this tax, they refrained from submitting requests. The ministry used external resources to set up a dedicated hotline for this population.

“3. The income-based parameters for determining eligibility for a discount in municipal taxes allows for a higher qualifying income the more people live in the household (unlike the parameters for receiving supplemental income from the National Insurance Institute). This gives an advantage to households with a larger number of members compared to a household with the same income but fewer members.”

MK Aryeh Deri did not respond to a request for comment by the time this article was published.