“When I get the content from one of my client’s cellphones, I know him better than he knows himself”

The use of personal information stored on the cellphone of Nir Hefetz – as well as the phones of Yonatan Urich and Ofer Golan, two of Benjamin Netanyahu’s former aides – provide yet further proof of how legislation and rulings in Israel lag far behind technology. Whether or not it ends in a plea deal, the trial of the former prime minister shows that, when a court allows police to look on our computers and cellphones, it gives them carte blanche to pilfer whatever information they want. Moreover, the police often use that information far beyond the scope of their investigation. “This is a far greater violation of privacy than a wiretap or a physical search.” A Shomrim follow-up.

The use of personal information stored on the cellphone of Nir Hefetz – as well as the phones of Yonatan Urich and Ofer Golan, two of Benjamin Netanyahu’s former aides – provide yet further proof of how legislation and rulings in Israel lag far behind technology. Whether or not it ends in a plea deal, the trial of the former prime minister shows that, when a court allows police to look on our computers and cellphones, it gives them carte blanche to pilfer whatever information they want. Moreover, the police often use that information far beyond the scope of their investigation. “This is a far greater violation of privacy than a wiretap or a physical search.” A Shomrim follow-up.

The use of personal information stored on the cellphone of Nir Hefetz – as well as the phones of Yonatan Urich and Ofer Golan, two of Benjamin Netanyahu’s former aides – provide yet further proof of how legislation and rulings in Israel lag far behind technology. Whether or not it ends in a plea deal, the trial of the former prime minister shows that, when a court allows police to look on our computers and cellphones, it gives them carte blanche to pilfer whatever information they want. Moreover, the police often use that information far beyond the scope of their investigation. “This is a far greater violation of privacy than a wiretap or a physical search.” A Shomrim follow-up.

Nir Hefetz, former spokesman of former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, is pictured outside a Jerusalem court house, November 16, 2021. Photo: Reuters

Chen Shalita

January 17, 2022

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

The personal information stored on the cellphone of Nir Hefetz, a former aide and confidant to Benjamin Netanyahu, coupled with police prying into cellphones belonging to Yonatan Urich and Ofer Golan, who also served as advisors to the former prime minister, is further proof of how legislation and rulings in Israel lag far behind the technological advances of recent years.

Is it possible that unbearable pressure was the reason Hefetz agreed to become a witness for the state against his former boss? The prosecution will insist that this is not the case and that the whole issue of the photographs is irrelevant. The defense, of course, will cling to any piece of evidence that suggests that Hefetz was encouraged to open up about the defendant. Either way, this is not the first time that Netanyahu’s trial, with all its complex branches, has shone a light on the darker corners of the law-enforcement system. Indeed, some would say that Netanyahu’s plan was to overthrow the system, more than to fix it. And still, the legal proceedings against him have highlighted lacunae that, when the defendant is an average citizen, are never addressed. It is only thanks to the massive interest in the trial of a former prime minister that these issues are finally being addressed properly.

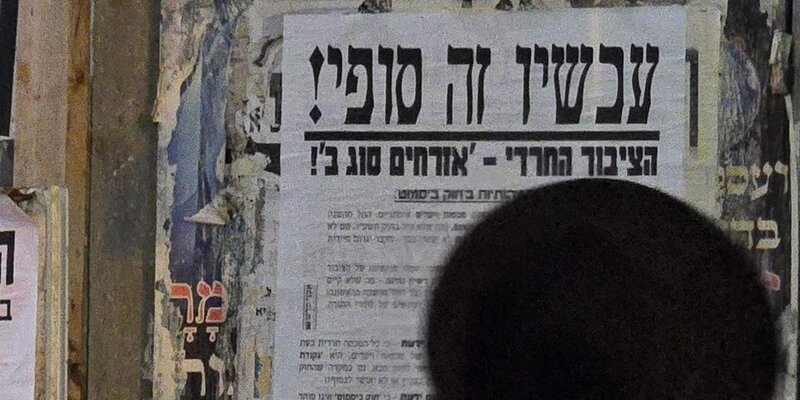

Earlier this month, for example, the Supreme Court ruled for the first time on how police should submit a request for a warrant to search a suspect’s cellphone. It also ruled on the level of detail needed and to what extent the courts should be allowed to exercise judgment. While it did permit police to examine the cellphones of Urich and Golan, who are suspected of harassing Shlomo Filber, a prosecution witness in one of the three pending criminal cases against the former prime minister, it criticized police for conducting an illegal search of Urich’s cellphone before requesting a warrant. Most importantly, it came out for the first time against the police’s tendency to search our cellphones in the hope of finding something incriminating.

Last month, Shomrim published an investigation into the police’s often problematic interrogation methods. Now, we can reveal the huge gulf between safeguarding suspects’ rights, including the right to privacy, and the liberties that the police have taken until now – with the courts’ approval – to examine in minute detail the daily habits and personal secrets that every single person has on their cellphones. It turns out not only that, when the courts issue a warrant permitting police to infiltrate our cellphones and computers, investigators are given carte blanche, but also that there is no follow-up on the searches or unauthorized snooping by police on the devices it confiscates.

“When I get the data that has been copied from the cellphone of one of my clients, as part of discovery process whereby police are obligated to share with material from an investigation, I end up knowing my client better than he knows himself,” says Yigal Balfour, head of Administrative Law for the Public Defender’s Office. “I know what terms he’s searched for and what keywords he’s entered, including those he’s deleted from his device’s history. The police have a program that can restore everything, including the exact locations he’s visited or when he used his device. Of course, I also know who he spoke to and at what time, and which apps he used. Millions of files with correspondence and photographs he’s sent and received, and where those photos were taken. There’s information there that you simply cannot imagine, because you restored a backup from an old phone, without knowing what’s on it. But the police can find it. Anyone who’s ever seen a report of information gleaned from a cellphone was shocked by the scope of the data.”