If it’s not Nir Hefetz, no one cares: In Israel, the law doesn’t apply in the interrogation room

Maltreatment – including denying sleep, drugs and medical attention. Threatening to ‘drop a bombshell’ that will cause great distress to family members. Humiliation, lies and – incredibly – rats and fleas. The high-profile arrests of Nir Hefetz, Shaul Elovitch and Moshe Hogeg have shone a light on some of the methods police investigators in Israel use to extract confessions from suspects. Unless you happen to be the head of a crime family, in which case the officer will bring you coffee and cake. Where is the line between acceptable and unacceptable deception? In Israel, there is no line. Unlike the United States or the United Kingdom, there are no laws protecting suspects’ rights. A special Shomrim report.

Maltreatment – including denying sleep, drugs and medical attention. Threatening to ‘drop a bombshell’ that will cause great distress to family members. Humiliation, lies and – incredibly – rats and fleas. The high-profile arrests of Nir Hefetz, Shaul Elovitch and Moshe Hogeg have shone a light on some of the methods police investigators in Israel use to extract confessions from suspects. Unless you happen to be the head of a crime family, in which case the officer will bring you coffee and cake. Where is the line between acceptable and unacceptable deception? In Israel, there is no line. Unlike the United States or the United Kingdom, there are no laws protecting suspects’ rights. A special Shomrim report.

Maltreatment – including denying sleep, drugs and medical attention. Threatening to ‘drop a bombshell’ that will cause great distress to family members. Humiliation, lies and – incredibly – rats and fleas. The high-profile arrests of Nir Hefetz, Shaul Elovitch and Moshe Hogeg have shone a light on some of the methods police investigators in Israel use to extract confessions from suspects. Unless you happen to be the head of a crime family, in which case the officer will bring you coffee and cake. Where is the line between acceptable and unacceptable deception? In Israel, there is no line. Unlike the United States or the United Kingdom, there are no laws protecting suspects’ rights. A special Shomrim report.

Moshe Hogeg, Nir Hefetz and Shaul Elovitch. Photos: Reuters, Shutterstock

Chen Shalita

December 23, 2021

Summary

Listen to a Dynamic Summary of the Article

Created using NotebookLM AI tool

T

wo public figures recently brought to the public’s attention an issue that tends to go unnoticed: the problematic methods that Israeli police employ and the harsh conditions under which suspects are held during questioning. The first public figure was businessman and owner of the Beitar Jerusalem soccer club, Moshe Hogeg, who is suspected of financial wrongdoing and crimes of a sexual nature; the other is Benjamin Netanyahu’s former media advisor Nir Hefetz, who is a state witness in the ongoing trial of the ex-prime minister.

Hogeg’s attorneys, Moshe Mazur and Amit Hadad, filed a complaint to the police, alleging that their client was questioned “after several nights without sleep, in a state of exhaustion and hunger.” The drive from interrogation center to the holding cell – a journey of no more than half an hour – took seven hours, they claimed. When he finally reached the holding cell at 11:30 PM, he was woken again at 2 AM, to be driven back to the interrogation center for another round of questioning, as if he were a terrorist with information about an imminent attack. When he told officers he was too tired to answer their questions, they told him that the alternative was to extend his detention. The holding cell itself, according to Hogeg’s lawyers, was infested by cockroaches and bugs and other detainees tried to extort their client with threats of violence against him and his family.

According to Hefetz, “on the second night, I woke up covered from head to toe in flea bites … I asked to see a doctor for two or three days. They told me that only the Israel Prison Service has a doctor, but by the time they brought me back to the holding cells, the doctor was off duty. When I asked to see a medic while I was being held by the Lahav 433 unit, I was given the runaround … Only when I collapsed on the floor of my cell did they send a medic … After a few days, a doctor came and saw my wounds and he told the investigators, ‘It’s not okay that he hasn’t seen a doctor until now’.”

In recordings of Hefetz’s interrogation, one of the officers is heard telling him: “In the next few days, a bombshell is going to shake your world. I’m not being sarcastic and I’m not kidding. I’m telling you that you ought to reconsider your path … Our modus operandi is very similar to the Shin Bet. We have the same capabilities. Your family unit is in grave danger now because of this bombshell. You won’t be the only one impacted by it.”

In the same case, members of the Elovitch family were also subjected to unworthy investigation techniques: police installed recording equipment in the attorneys’ consultation room at the detention center – a space that is supposed to allow for confidential discussions between lawyers and their clients. In that room, Elovitch met with his son, Or, who tried to convince him to fire Jack Chen as his lawyer, since, according to police investigators, Chen was advising Elovitch not to turn state’s evidence.

The head of the Israel Bar Association, Avi Himi, wrote a letter to the attorney general in response to these allegations. “It is impossible to remain indifferent when police abuse the belief that meetings between an attorney and his client are confidential … And it is certainly impossible to remain indifferent to the moral lines that have been crossed, to the exploitation of a son against his father … Every person has the right to chose which lawyer represents him and for that lawyer to advise him without worrying that, if he fails to please the police, he will be fired.”

“There’s no law and police guidelines are amorphous”

So, what’s permissible and what’s not during police interrogation? How does the law define fair questions, which protects the fundamental rights of the suspect? What limitations are there on questioning a suspect in the middle of the night? Shockingly, there is no such law.

“The law is silent when it comes to suspects’ rights,” says Tzipora Gitter, the head of prisoner representation at the Public Defender’s Office in Haifa, where she focuses on interrogation conditions. “This is very different from somewhere like the United Kingdom,” she adds, “where these things are anchored in law. The Criminal Procedure Law deals with detainees’ rights, not with conditions in the interrogation room. It took many years for Clause 9, which deals with these conditions, to be drafted – and even that leaves a lot open to interpretation.”

Official police instructions should get rid of any ambiguity. I asked the police to see them, but I wasn’t deemed worthy of a response.

“Police procedures are not made public and they are not adhered to. In every European country, suspects have clear rights: there are breaks in questioning every two hours, because a study published in the U.K. found that the average length of an investigation that led to a false confession was two hours and 16 minutes. Detainees must be given a minimum of eight hours sleep. British police also confront suspects with harsh allegations, but their attitude is more humane.”

Gitter: "They even question suspects who are under the influence of drugs or alcohol. There’s no obligation to provide medical services or medicine at the start of the interrogation. They will be provided at some stage, but people who suffer from chronic conditions will be questioned even if they do not feel well and won’t see a doctor for days"

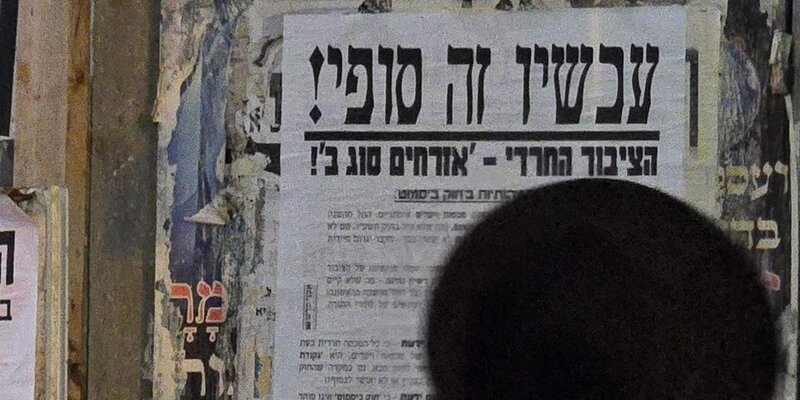

With their testimony, Hefetz, Elovitch and Hogeg became the public face of the interrogation methods used in Israel, known in the profession as subterfuge. This involves using pressure on a suspect – the limits of which are not anchored in any law. However, since the subjects of these methods usually have a far lower public profile and are generally considered far less upstanding than the above-mentioned gentlemen, the manipulation they face is met, for the most part, with indifference.

“When the media was up in arms over Hefetz’s descriptions of his questioning, in our office the response was, ‘We see this – and a lot worse – every single day’,” says Michal Orkabi from the Tel Aviv Public Defender’s Office, where she oversees police interrogation techniques. “I’m delighted that the issue is finally on the agenda. Just think – these are cases when officers saw the suspects as human beings just like them; they didn’t treat them like human garbage, which is often the case when they’re questioning criminals.”

One veteran criminologist who spoke to Shomrim agrees with Orkabi’s assessment. “The things that Hefetz complained about are some of the less grievous cases I’ve heard of,” he says. “I would describe them as unpleasant, but not terrible. I’ve had clients who spent their entire detention in cells with fleas and rats. Some were left for three weeks in nothing but the same T-shirt and underpants. But when a former adviser to the prime minister is involved, it hits the headlines; when it’s someone called Buzaglo from the South, he’s fair game.”

Clause 12 of the evidentiary regulations is supposed to help suspects. It determines that a confession must be given freely and willingly. “The question is what does ‘freely’ mean,” Moshe Mazur, one of Hogeg’s lawyers, told Shomrim. “If someone hasn’t slept for 24 hours or hasn’t been given enough food, is he speaking freely? There’s no clear boundary here.”

In the end, a lot depends on the conscience of the investigator.

“That’s true. In the United States, things are a lot clearer. The Constitution determines what’s permissible and what is not. Here, there’s no such law, and police procedures are amorphous. Here, we talk about ‘reasonable time’ for sleep. How many hours is that? It’s unclear. The Israel Prison Service has guidelines regarding prisoner sleep and food. Can I tell you that they abide strictly by those guidelines? No, I can’t. Very often, there’s be a ping-pong between the police and the IPS, each side refusing to accept responsibility. The IPS claims that the police drag interrogations on into the small hours, while the police argues that this is needed for the investigation (even though in many cases there’s no justification for it). It also says that the time it takes to get the suspect from the detention center to the investigation room is not in its control. So, the suspects fall between the cracks.”

When it comes to sleep, there have been some truly absurd allegations. “The state must allow a suspect six hours of sleep – unless the police believe that there’s reason to think somebody’s life is in danger or the efficiency of the investigation could be compromised,” says Gitter. “What could compromise an investigation? That’s a good question. We’ve secured an acquittal for someone accused of burglary because he was half-asleep when he was questioned. In the video, you clearly see an officer questioning a suspect who’s asleep and that was the basis for an indictment to be filed.”

Good job there’s documentation.

“Not always. In Israel, police only need to document investigation dealing with serious crimes, those with at least a 10-year sentence. Lesser crimes don’t need to be documented. Here and there, some interrogations are recorded. When the suspect has psychological problems, for example.”

How is someone with psychological issues questioned?

“In Israel, someone with psychological problems or mental issues is questioned the same as everybody else. Here, they even question suspects who are under the influence of drugs or alcohol. There’s no obligation to provide medical services or medicine at the start of the interrogation. They will be provided at some stage, but people who suffer from chronic conditions will be questioned even if they do not feel well and won’t see a doctor for days. Police conduct lengthy interviews with people suffering from diabetes or high blood pressure who feel unwell, have dizzy spells, headaches, are confused and not given their medication on time. In the United Kingdom, in contrast, a suspect suffering from epilepsy or diabetes must be examined before being questioned, to make sure he or she is fit to answer.”

Have you managed to stop it in real time?

“Sometimes we’re aware of the severity of a situation only after the investigation is completed and an indictment is filed. People confess just to put an end to the questioning and that’s very frustrating. Detainees lose their freedom – not their humanity and not their basic rights.”

It turns out that police can even bypass the occasional documentation of interrogations that Gitter described. “Suspects have told me how they are prepped before a videotaped interview,” one private defense attorney told Shomrim. “When police see that, in the middle of the questioning, things are going in a direction they don’t like, they let you out for a cigarette break, a coffee or the restroom – and they reinforce the kind of testimony that they want to hear. No one knows what happens during those breaks. Unless it’s Hefetz or Elovitch, no one cares.”

The interrogations

“Let the legislators put it in writing: Police can lie and deceive”

The situation, as it exists in Israel today, leave police with broad freedom of operation. Only the courts can stop them and they often do so too late, when the damage – both psychological and to the investigation – has already been done. How is it possible that Israeli lawmakers have not yet address this issue? “Nobody cares about criminals,” explains public defender Orkabi with understandable sarcasm. “And people are more forgiving when it comes to misleading rapists and murderers. The feeling is that it’s okay to punish them from the moment they are arrested – but the system doesn’t include fleas, lack of ventilation, cold in the winter and heat in summer. Keeping suspects in these conditions causes grave societal harm, because they then say to themselves that, since they’re already being treated like animals, then maybe they should behave like animals. Criminological studies across the world show how detrimental it is to a society to treat people like animals – and you can only imagine what they found.”

And yet the public sees no urgency in defending suspects’ rights?

“Because normative people are sure it won’t happen to them. We won’t be questioned and we won’t be arrested. But it can happen to anyone. According to figures, only 50 percent of people arrested are ever put on trial; the rest were questioned and detained for nothing. Even innocent people, who were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, can find themselves behind bars for a week, until police are persuaded that they were not involved. But the trauma leaves scars for many years. I have clients who are still suffering. They pay a very high price for that week.”

What scars them?

“They are handcuffed and manacled during questioning, so of course they’re afraid. They’re in a police interrogation room, so they have nowhere to go. It’s a kind of sting operation. The police are categorizing them as criminals. And then there are the lies. It is permissible for a police officer to pretend to be a rabbi and to advice the suspect to confess? Someone seeks advice from a person he sees as a spiritual authority, only to discover that he’s on ‘The Truman Show.’ One judge ruled that it’s not admissible, but he accepted the confession in that case anyway. Many time, the courts simply reprimand the police and ask almost rhetorically to what extent the confession was obtained by subterfuge. In the end, they convict, because they were dealing with a murderer.”

If everyone confessed just because an investigator asked them to, then the police wouldn’t need subterfuge.

“Without subterfuge no one would talk? No problem. The legislators should sit down and write a law that stipulates that it’s permissible for the police to lie and deceived. That an investigator can tell suspects that their fingerprints were found at the scene or that their DNA was found on the body of a rape victim – even though that’s no true. The norm today is that it’s okay to lie, but not to forge documents. An investigator can tell a suspect that his friend has confession, but he cannot show him a forged confession. We have clients who can’t even read, so what difference does that make to them? And still, one type of subterfuge is permissible while another isn’t. The differentiation was made after police officers fabricated court records and presented them to a suspect as real – but the judge ruled that was unacceptable. That was the watershed moment. So, police can’t forge a written confession, but they can lie verbally. As much as they want. I have a serious problem with an officer being allowed to lie for hours on end.”

Is it possible the reticence to legislate stems from a desire not to expose these methods, thereby losing the element of surprise or limiting investigators’ scope for creativity?

“We are well aware of the police’s methods. They’re no secret. And criminals know them even better than we do. Not only would a law of this kind not put an end to creative investigations, but it would also force the police to be genuinely professional and to look for evidence, rather than trying to break down a suspect. The goal of interrogations, as they are conducted today, is to make the suspect as small as possible. To ride roughshod over you. To crush you and tear you apart. And, from within those smashed pieces, to ask you what you did wrong.

“I consider myself to be a strong person, who understands the law, but I know that after two days of questioning, I wouldn’t be the same person. Many times, what happens crosses a line. It’s inconceivable that you detain someone until they confess or say what you want them to say. The police would never admit that’s their system, but it exists. And when you see someone confess, even when it’s a false confession, it’s very hard to let go of that and hard to believe that someone would confess to a crime they didn’t commit.”

Justice Minister Gidon Sa’ar’s proposed legislation on disqualifying confessions says that all it takes is for due process to be violated for a court to throw out a confession. Will that put an end to the phenomenon?

“The proposal only refers to evidence obtained illegally, but if police can lie and deceive, and can hold someone in harsh conditions, then there’s nothing illegal. Investigators didn’t do anything illicit for the very simple reason that they’ve never been told not to behave in this way.”

Give us an example of manipulation that infuriated you.

“They once questioned someone while her young daughter was waiting outside the interrogation room. In the middle of questioning, she suddenly asked, “Who can I hear?” and the police told her that her daughter was here by chance, on her way to an emergency shelter. That was no coincidence. A police station is a big place; you shouldn’t be able to hear everything that happens there. The whole idea was to crack her a little bit more. There were other places a little girl could wait. It didn’t have to be outside the interrogation room.

“And, you know what? There doesn’t have to be a flea infestation in the holding cells. The fleas are in the mattresses, so the guards aren’t affected. But anyone who lies down on one of those mattresses will get bitten. When the Public Defender’s Office inspects the holding cells, we can smell the fresh paint, because they’ve been preparing for our visit. They tell us that they disinfect the cells, but that the detainees bring fleas. I don’t buy it. It’s a problem that can be solved – just like they dealt with the Coronavirus. It’s a matter of will.”

The Investigators

“We didn’t order the fleas especially for Nir Hefetz”

Former police officers admit that, when it comes to conducting interrogations, there are many gray areas. “The police will always walk close to the line; the subterfuge that an investigator uses is designed to achieve things they wouldn’t get otherwise,” says Yair Regev, a former police investigator who now works as a public defender. “You could say that everything is permitted, apart from what the Supreme Court explicitly said is unlawful. Over the years, there have been more and more ruling and the courts are becoming more protective of suspects’ rights.”

“It’s hard to write guidelines for conducting an investigation, because it’s a very amorphous and creative area,” says former police Commander Meir Gilboa, who used to be the deputy head of the International Crime Unit. “Even if there were clear guidelines, I don’t know to what extent they would be internalized. When it comes to identity line-ups, the Israel Police has one of the best protocols in the world. But let’s admit it – they don’t always act in accordance with the rules. They often cut corners. Only a handful of righteous officers will look at the guidelines before holding a line-up. Plus, there are hundreds of such guidelines in the police. I’d eat my hat if you could fine one in five officers who know 10 percent of the rules.”

How depressing.

“Not at all. In any case, the complex investigations are conducted by the Lahav 433 unit, where there are experienced and serious officers who have the relevant training. All of them are lawyers, economists or accountants. The officers in that unit don’t have to deal with the very heinous crimes that can lead to harsh confrontations.”

Orkabi sees things very differently. “It is precisely in the more complex and convoluted investigations that the lines are easier to cross. And that’s got nothing to do with the intelligence or education of the officers. It’s the system. A system that allows for interrogations in which anything goes. The question is to what extent we allow it and, at the moment, most of us are perfectly okay with it.”

Agami-Choen: "It’s not a crime to shout and I agree that a police interrogation shouldn’t be a picnic. But unfortunately, I have now been exposed to unworthy acts committed against good, normative people, who could have encouraged to talk without profanities and without humiliating them"

Retired Commander Ziva Agami-Cohen, the former head of the police fraud division and now a private attorney, sees both sides of the argument – perhaps she has seen the issue from both sides. “During my time in the police,” she says, “I took interrogations very seriously; I saw them as the heart of policework, that should be conducted cleverly and using subterfuge. Exposing the truth is, in my opinion, the most important thing – but not, of course, at any price. The use of force, for example, is always unacceptable, but our approach was that criminals can’t complain, since their actions got them into the situation to begin with.

“Now, I have clients who were not involved in any criminal incident, who find themselves subjected to shouting and humiliation in the interrogation room, until they break down in tears. A grown man crying is an embarrassing sight. It’s not a crime to shout and I agree that a police interrogation shouldn’t be a picnic. But unfortunately, I have now been exposed to unworthy acts committed against good, normative people, who could have encouraged to talk without profanities and without humiliating them.

“As a media adviser, Nir Hefetz is more than capable of expressing himself and, thanks to his public standing, he was able to send out a clear message; as a result, the media dealt with almost nothing else for several days. Criminals, no matter how ‘senior,’ can’t send out the same message, because no one cares about them. This is a moment that society should utilize.”

Give me an example of one change that needs to happen.

“It’s time to consider allowing attorneys to be present during interrogations. We don’t have to copy the American system; we can decide when the presence of a lawyer is mandatory and when it isn’t. I used to think that no criminal would confess with a lawyer sitting next to him, and that would increase the crime rate. Today, I think that a confession is not the be all and end all and that police should work harder to find evidence other than a suspect’s confession. Even if, as a result, more confessions are deemed inadmissible, we have to ask ourselves how far we, as a society, are willing to go to reduce crime.

“The state has a lot of power in its dealing with citizens and the police can and should be more professional, to get more resources and to act in a more sophisticated manner. When questioning public figures, for example, the police conduct a covert investigation before they arrest the suspect in an effort to obtain more evidence. In the Holyland case, for example, police didn’t need Ehud Olmert to confess in order to submit a file to the prosecution.”

Investigations in prime ministers usually have more funding than routine investigations.

“It’s not just about the money. It’s also about professionalism. You can impose a blanket ban on trickery during interrogations, but there must be a clear boundary. There are internal guidelines, there is the experience garnered by police over the years and there are rulings which address the issue of interrogation-room subterfuge. Trickery cannot include the abrogation of suspects’ rights and such behavior should be illegal.”

London: "A police interrogation isn’t a job interview or an episode of ‘This Is Your Life,’ it’s a deeply unpleasant experience. And part of the police’s tactics is to break your spirit, to make an impression, to threaten and to insult"

But it still happens. Yaron London is another former police officer from the Lahav 433 unit who now works as a private defense attorney. Every officer knows that he can apply psychological pressure and, for normative people, who aren’t used to being in the interrogation room, that can be traumatic. A police interrogation isn’t a job interview or an episode of ‘This Is Your Life,’ it’s a deeply unpleasant experience. And part of the police’s tactics is to break your spirit, to make an impression, to threaten and to insult.”

I understand it can’t be sterile, but where’s the line?

“It’s a question of interrogation ethics. There are some things that police are taught in courses not to do: no physical violence and no threats against family members. There are some things that are in a gray zone, where each officer decides for him or herself where the line is. The moment you understand that there’s no free will here, but, rather, a kind of gun to the head, you’ve crossed the line.”

Is the line different for every officer?

“Obviously. Just like they didn’t order fleas especially for Nir Hefetz. Those are the conditions in Israeli holding cells. It’s not the Plaza and anyone who’s used to sleeping on a comfy mattress and with air conditioning might feel like it’s the end of the world – but that’s the situation. People don’t close their eyes in a holding cell; partly because of the fleas or their aggressive cellmates, and partly because they are worried and nervous because they’ve been arrested.

“For one detainee, it would be the end of the world if his wife found out what secret he’s been hiding and he’ll do anything to prevent that from happening. Someone else might not care about his wife finding out. For low-level members of a criminal organization, nothing is really a great concern, but for a white-collar criminal, who finds the rug pulled out from beneath his feet and who can’t go to the bathroom without permission – it’s a shock to the system.”

Do you hold simulations for your clients before interrogations?

“Sometimes. I also remind them that it’s not forever. That there will be situations where they are shouted at or insulted and that they should either hold their tongues or ask for the officer’s superior. The critical stage of every interrogation is the first stage. The first hours will determine the outcome of the case. If a defense attorney were present, it would be different. In Israel, a suspect can consult with their attorney before questioning, but then the attorney leaves the room. In some countries, the attorney is present at all times and can offer real-time advice.”

That serves the interests of the suspect. The question is whether it also help solve the case.

“Are you saying that in the U.S. and Britain they don’t solve cases? They just do a more thorough job, that’s all.”

The judges

“Israeli judges aren’t sending police the right message”

Why are police investigators so motivated to extract a confession or incriminating evidence? “Because in Israel, a single piece of evidence is enough for a conviction,” according to Prof. Boaz Sangero, founder of a website dedicated to criticism of the criminal justice system in Israel and of the Institute for Safety in the Criminal Justice System at the Western Galilee College. “There’s a systematic failure here: the more energy the police invest in getting a suspect to confess or to incriminate someone, and uses subterfuge and jailhouse snitches to get them, there’s more chance of obtaining them but they will be less and less useful as it will be impossible to know whether they are genuine. Police methods test a suspect’s endurance and not their truthfulness.”

So, police are just trying their luck? They take a risk in the gray area and if the courts don’t slap them on the wrist, they’ve got a confession?

“Correct. In the past, suspects would be beaten. Today, the police use psychological means to wear the suspects down and to get them to confess; sometimes, these methods are used against witnesses. Unfortunately, Israeli judges are not sending the right message to these police investigators; the message should be not to focus on the suspects, but to find independent additional evidence. There needs to be a change in the law whereby convictions cannot be given on the basis of a confession alone, or any sole piece of evidence or testimony.”

How does the situation here compare with the rest of the world?

“In Israel, we’re still stuck with the aggressive American system known as the Reid Technique. According to this technique, suspects are lied to, shouted at, worn down and put under intense pressure to confess of give incriminating evidence against someone else. In the United Kingdom, they have adopted a more progressive method, called the PEACE method of interrogation, whereby investigators listen to a suspect with an open mind and then confront him or her with the evidence – without lying to them. They get much better results this way.

Gilboa: “It’s hard to write guidelines for conducting an investigation, because it’s a very amorphous and creative area/ Even if there were clear guidelines, I don’t know to what extent they would be internalized”

“There are some European countries where police are not allowed to lie to suspects, since they represent the public and must act fairly; also, because these lies lead to false confessions and false allegations. Unfortunately, Israeli judges view police subterfuge as a legitimate tool of interrogation. They almost never refuse to accept a confession; they accept almost 100 percent of them and then use them to convict. Police investigators will only get the message and improve their interrogation techniques once judges start tossing out illegally gained confessions. In the meantime, we’re stuck with a system in which innocent people and the guilty confess; and almost everyone is convicted.”

Is the proposed legislation that would disqualify illegally obtained evidence a step in the right direction?

“The Yissacharoff Doctrine [which determines that a court has the right to reject illegally obtained evidence] and Sa’ar’s proposed legislation stop short. They only refer to a confession or testimony that was illegally obtained. Because Israeli police investigators often use illicit means, it would have been better to include all the fruits of that poisonous American tree, so that not only would illegally obtained evidence be inadmissible, but so too would anything obtained as a result of that evidence.”

Who loses out from the current situation? The truth is that everyone does. The normative people who slipped up and were recognized as the weak link, which could break easily and on whom it makes sense to apply maximum subterfuge and pressure. And the criminals who suffer the same treatment again and again – without anyone caring. Surprisingly, the only people outside of this circle are senior criminals – the heads of organized crime families. According to one senior defense attorney, “when it comes to crime bosses, police offer them coffee and cake.”

Metaphorically?

“Not always. Police have a respectful attitude toward them, because they know that’s the most effective way. They know that they won’t catch a crime kingpin by putting a snitch in his cell, because the hardened criminals can under weeks of questioning without breaking. The harsh conditions are harder for people without prior experience of such things, for people from good homes, who are not habitual or career criminals. These people are traumatized. And they are the people who will break after one night sleeping with fleas.”

When you put it like that, is there any point even questioning criminal bosses?

“First of all, we have to. Secondly, they can sometimes say something they didn’t mean to say, out of carelessness or arrogance. In the end, it’s not math. There’s a whole, complex world around it, which means police need to talk differently to everyone. Think about an officer from Lod interrogation a senior criminal from that city. The criminal knows the officer’s parents and family. The officer wouldn’t dare raise a hand to him – because of the consequences and because it wouldn’t be effective.”

What forms does the psychological pressure take?

“We tell people that if they’re sent to prison, their spouse will divorce them. We encourage them to turn state’s witness – before it’s too late. Sometimes we’ll even bring the suspect’s wife in to help persuade him to turn state’s witness. We’ll talk about relocating them to a new country to start a new life in witness protection.”

Are there more sophisticated mind games?

“There was a murder case in which bite marks were found on the victim’s body. We asked the suspect for a casting of his teeth, but he refused. Since they couldn’t force him to give one, they brought him a fancy breakfast, with big pieces of cheese – because the forensics lab wanted a soft material. The moment he took a bit from the cheese, they grabbed it from him and rushed it to the lab.”

The cheese trick looks like child’s play compared to the experience of a client of Avi Himi, who was suspected of rape. “The man, who worked as a car appraiser, was summoned to a job near a local moshav,” Himi says. “Police investigators masqueraded as criminals and wanted him to admit to committing rape. The told him: We know where you live. They showed him photographs of his wife and child. They didn’t warn him and didn’t tell him they were police officers. In the end, the man was convicted because of DNA evidence, but what if he had confessed just because he was afraid? Suspects have rights.”

Change is on the way? The proposals on the agenda

As things currently stand, defense attorneys are pinning their hopes on the courts. Or, more accurately, on several rulings that have become central to the issue of fair interrogations. They are also pinning hopes on a series of legislative measures being pushed by Justice Minister Gidon Sa’ar. However, none of them address the most important issues, such as lying during an interrogation, subterfuge and jail-house snitches. These phenomena will, it seems, be with us for a while longer, unless the Public Committee for the Prevention and Correction of False Convictions, headed by former Supreme Court Justice Prof. Yoram Danziger – which has already submitted an interim report on the issue of forensic evidence – offers clear recommendations on the matter. Tzipora Gitter, who is on the committee, told Shomrim that, “when we have a discussion on false confessions, we will also talk about interrogation methods and whether the time has come to impose different restrictions.”

At the request of Shomrim, Yishai Sharon, the head of investigation and policy at the State Defender’s Office, has summarized the proposals on the agenda:

1. Disqualifying evidence

This proposal would enshrine in the law the Yissacharoff Doctrine and various ruling that came in its wake and would give the courts wider and more flexible discretion to disqualify evidence in instances where the suspect’s right to due process was fundamentally violated. According to the bill, which passed its first Knesset reading in November and is now being discussed by the Constitution, Law and Justice Committee, that will include evidence given by a witness and not just a confession from a suspect.”

Why does the proposal not address the issue of evidence obtained as a result of illicit evidence – the so-called fruit of a poisonous tree?

“Because there were disagreements among members of the committee that formulated the legislation and, in the end, they reached a compromise that gives the courts discretion. The prosecution and the police wanted to limit that discretion even further, and the justice minister adopted the majority view, espoused by judges and the Public Defender’s Officer, to give greater leeway.”

2. A Basic Law on Legal Rights

This proposal seeks to enshrine various rights within criminal law – from the investigation stage to the trial – to allow courts to give greater weight to violations of suspects’ rights. The proposal is being discussed in the Justice Ministry and Sa’ar has declared that he intends to bring it to the Knesset during its upcoming session.

3. The Suspect Interrogation Bill

This government-sponsored bill is the most significant in terms of suspects’ rights. It was first proposed by former justice minister Ayelet Shaked in 2018 but has not moved on since then. The proposal would enshrine in law the rights and obligations of anyone questioned by police – suspects and witnesses – and the equivalent rights and obligations of the investigators. It contains clauses relating to how interrogations are handled and the plan is to add detailed instructions regarding sleep, night-time questioning and food.

Orkabi is optimistic. “It will take time, but, in the end, it will happen. These lies, this trickery, this system that grinds people down until they can’t take it anymore. In the end, it will disappear.”

Israel Police response

“Interrogation rules are determined by the law”

“The Israel Police operates by the authority of the Police Directive, which authorizes it, inter alia, to conduct investigations where there is a suspicion of criminal activity. The regulations regarding interrogations are determined by law – the Criminal Procedure Law – and are supervised by officials from the police, the State Prosecution and the Police Protection Unit.”

In response to this, Shomrim asked the police for specific references to the relevant clauses in the Criminal Procedure Law and for clarifications on the nature of the supervision. “Our response has been filed and we have nothing else to add,” a police spokesperson said.